The Swift Rise and Apparent Demise of “Jesus’ Wife” -- Sightings

From Jesus Christ Superstar to the Last Temptation of Christ and on to The Da Vinci Code inquiring minds have wanted to know -- did Jesus have a wife and kids? For some the question is blasphemous because somehow sex is linked to sin, so if Jesus is without sin then surely he couldn't have been married. For others it's an irrelevant question -- there's no biblical or even historical record/account to suggest he was married (nor that he wasn't if you want to go by an argument of silence). For still others the idea that Jesus had a wife is intriguing and maybe even humanizing. So, when word came about a major textual discovery suggesting Jesus had a wife, it caught the attention of the world. Now, the controversy has died down quite a bit, in part because scholars have raised questions about the genuineness of the manuscript fragment that led some to imagine the possibility. Two Ph.D. candidates, Trevor Thompson and David Kneip update us on the status -- in case you're interested -- of this controversy in this week's Thursday edition of Sightings. Personally I don't get too excited about controversial discoveries -- they usually amount to nothing, but this is an interesting case study of how the historical process is undertaken. So, take and read, and offer thoughts.

****************************

Martin Marty Center for the Advanced Study of Religion

The University of Chicago Divinity School

Sightings 10/25/2012

The Swift Rise and Apparent Demise of “Jesus’ Wife”

-- Trevor W. Thompson and David C. Kneip

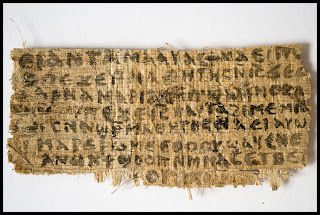

On September 18, 2012, Prof. Karen L. King of Harvard Divinity School made public the so-called “Gospel of Jesus’ Wife” at a conference in Rome. The text, written in Coptic (the form of Egyptian spoken in the early Christian period), is preserved on a codex papyrus fragment (4 x 8 centimeters) with eight visible lines on one side (the other side is heavily faded). The fragment seems to come from the middle of a page, with lost text on either side of what is visible, as well as above and below. King argues that the fragment is from the fourth century CE and is likely a translation of a second-century CE Greek original.

Most likely, readers will have heard of this papyrus due to the content of the fourth and fifth lines: the fourth line reads, in part, “Jesus said to them, ‘My wife...’”; the fifth line includes “she will be able to become my disciple....” The texts of the New Testament make no mention of Jesus being married. The canonical Gospels do mention some women as being part of Jesus’ “circle” (cf. Luke 8:1-3). The papyrus raises questions both concerning Jesus’ marital status and about whether women might have been included alongside men in the group called “the disciples.”

As part of her publishing the fragment, King gave an interview to reporters, provided high-resolution images and a transcription of the Coptic text (with adjoining English translation) on the HDS website, and posted a draft of her article on the papyrus scheduled to be published in Harvard Theological Review in January 2013. Not surprisingly, news of the fragment spread quickly as major news outlets around the globe carried the story. Bloggers both academic and popular debated various issues surrounding the papyrus; scholars posted academic papers directly to the Web; NPR covered the story on “All Things Considered”; and even YouTube videos appeared discussing various aspects of the problem.

One special difficulty has concerned the papyrus’s provenance; the antiquities market in the Middle East is notoriously complex, and very little is known with certainty about this fragment’s origin. But the doubts about the papyrus extend beyond this matter even to its authenticity as a whole. As part of its standard protocol for vetting potential publications, HTR consulted three anonymous reviewers regarding King’s essay. As she notes, one reviewer accepted the fragment as genuine, a second raised queries, and a third asked serious questions about the grammar and handwriting. This mixed response has continued: while at least one papyrologist and an expert in Coptic grammar have affirmed aspects of the fragment as genuine, others have not been so sure.

Francis Watson, from the UK’s Durham University, was one of the early detractors of the fragment’s authenticity; he argued that significant material in the text derives from the Gospel of Thomas, and specifically from a modern print edition of that text. Leo Depuydt of Brown University has come to similar conclusions, with his views scheduled to be published in HTR alongside King’s publication. Finally, Andrew Bernhard, connected with Oxford University, has discovered what seems to be a “typo” in the “Gospel of Jesus’ Wife” that is also present in a widely-distributed electronic interlinear transcription and translation of the Gospel of Thomas. For these reasons, at the time of this writing, the tide of scholarly opinion seems to be turning decidedly against the authenticity of the fragment.

On the chance that the papyrus fragment turns out to be legitimate, we should say that Jesus' reference to “my wife” can be understood in a number of different ways. It is possible that some second- to fourth-century Christian(s) thought that Jesus was married in the way that we understand it today, but we must also remember that Gnostic groups with Christian affiliations used language of marriage and family (including the concept of "spiritual marriage") with great fluidity during those centuries. Regardless, the papyrus and its reception again demonstrate an insatiable appetite in the media for controversial “discoveries” concerning the origins of Christianity; this appetite will surely continue to manifest itself in the future.

References

The full text of the Gospel of Thomas is available here.

Trevor W. Thompson is a Ph.D. candidate at the University of Chicago in the Department of New Testament and Early Christian Literature.

David C. Kneip is a Ph.D. candidate at the University of Notre Dame in the Department of Theology.

----------

This month, the Religion and Culture Web Forum presents a chapter from Naomi Davidson's recent book Only Muslim: Embodying Islam in Twentieth-Century France (Cornell 2012). Davidson's monograph tackles the question of why the French state (and its citizens) interacted with Muslim immigrants throughout the 20th century exclusively through their Muslim identity. The answer to this question, she argues, lies in the embrace of a notion of "French Islam," which "saturated [immigrants] with an embodied religious identity that functioned as a racialized identity. The inscription of Islam on the very bodies of colonial (and later, postcolonial) immigrants emerged from the French belief that Islam was a rigid and totalizing system filled with corporeal rituals that needed to be performed in certain kinds of aesthetic spaces. Because this vision of Islam held that Muslims could only ever and always be Muslim, 'Muslim' was as essential and eternal a marker of difference as gender or skin color in France" (1-2). Davidson's chapter on 1970s Paris addresses why the "conflation of Muslim religious sites with racial, national, and cultural identities" continued even in an era when Muslim religious observance in France was widely regarded as "on the wane"; this state of affairs reveals, according to Davidson, "the deep-seatedness of the French belief in the fundamental inability of certain Muslim immigrants to be anything other than Muslim subjects" (171).

----------

Sightings comes from the Martin Marty Center for the Advanced Study of Religion at the University of Chicago Divinity School.

Comments