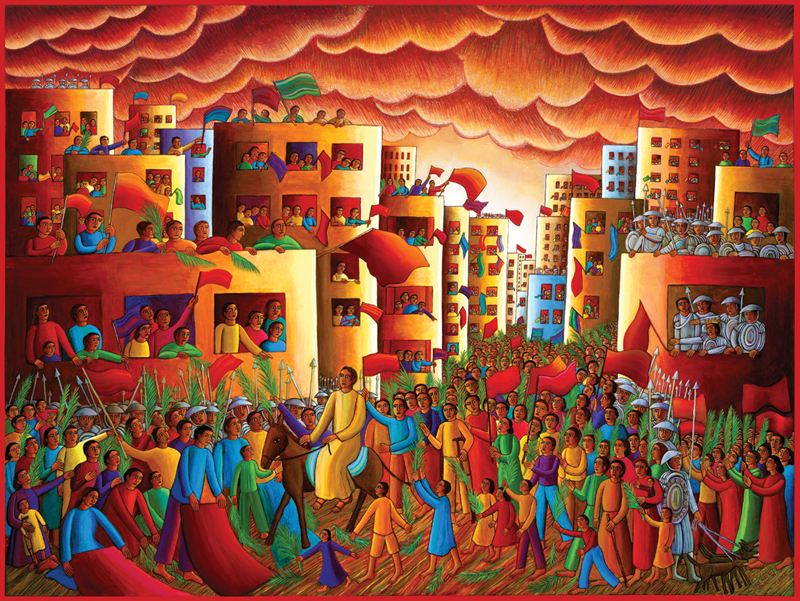

Palm Sunday's Subtle Political Message - Lectionary Reflection for Paul Sunday (Luke 19)

Luke 19:28-40 New

Revised Standard Version (NRSV)

28 After he had said this, he went on ahead, going up to Jerusalem.

29 When he had come near Bethphage and Bethany, at the place called the Mount of Olives, he sent two of the disciples, 30 saying, “Go into the village ahead of you, and as you enter it you will find tied there a colt that has never been ridden. Untie it and bring it here. 31 If anyone asks you, ‘Why are you untying it?’ just say this, ‘The Lord needs it.’” 32 So those who were sent departed and found it as he had told them. 33 As they were untying the colt, its owners asked them, “Why are you untying the colt?” 34 They said, “The Lord needs it.” 35 Then they brought it to Jesus; and after throwing their cloaks on the colt, they set Jesus on it. 36 As he rode along, people kept spreading their cloaks on the road. 37 As he was now approaching the path down from the Mount of Olives, the whole multitude of the disciples began to praise God joyfully with a loud voice for all the deeds of power that they had seen, 38 saying,

“Blessed is the kingwho comes in the name of the Lord!Peace in heaven,and glory in the highest heaven!”

39 Some of the Pharisees in the crowd said to him, “Teacher, order your disciples to stop.” 40 He answered, “I tell you, if these were silent, the stones would shout out.”

*******

It's Palm

Sunday. After two years of COVID-19 restrictions, we might be ready to bring back some of the Holy Week traditions, starting with a triumphal entry into worship. So, why don't we join the crowd in Jerusalem and welcome Jesus back to church waving palm branches? But, let's not get ahead of ourselves. Remember that Jesus' triumphal entry leads to crucifixion.

If you

read the story closely it appears that Jesus was trying to trigger a

reaction from the crowd heading into Jerusalem ahead of the Passover celebration. It’s not like he didn’t know

what was going to occur when he decided to ride a colt into Jerusalem. It is a

rather apocalyptic moment that draws upon biblical imagery and unsettled

political conditions. With tensions running high in the city, it wouldn’t take

much to ignite a protest and even a revolution. The Roman overlords didn’t take kindly to such

things. Many within the religious leadership in Jerusalem would have also been

aware of the effects of provocative actions. It was in their best interest to

keep things under control, especially when this was one of the biggest

pilgrimage events of the year.

So,

what was Jesus up to? The image of the colt draws on Zechariah 9:9. That

post-exilic prophetic book offers a picture of a messianic figure

riding into Jerusalem on a colt “triumphant and victorious” (Zech. 9:9). So

when this charismatic preacher and healer decides to ride into the city on a

colt, at least some in the crowd would have caught on. Then we hear words of

praise offered up, words drawn from Psalm 118: “Blessed is he who comes in the

name of the Lord” (Ps. 118:26).

Let’s

put ourselves into the shoes (sandals) of the pilgrims streaming into Jerusalem for this big

annual festival. Festivals are always emotional events, especially when the

festival celebrates the nation’s liberation from slavery. If you’re living

under the yoke of foreign rule, you might pick up on any sign that one’s

overlords might be overthrown. At least some in that crowd might have envisioned this young prophet being a messianic figure who could take on the powers that be. The question is: what are Jesus' intentions? It's easier to read the crowd than Jesus.

In the end, this triumphal entry into Jerusalem leads to tragedy (the cross). Something seems lost in translation. There is

much standing in the background that we simply don’t understand. It is

important to remember that Judaism wasn’t monolithic then or now. It wasn’t

simply Jesus against the Jews or the Romans. Jesus was a Jew operating within a

Jewish context. So was he a politicial provocateur? Possibly? Did he have political

intentions? In the first century anyone even hinting at revolution, religious

or political, would be suspect.

As I

ponder the reading for Palm Sunday, the question of how we understand the relationship of church and state is pertinent. Here in the United States, there are a number of movements that either want to merge church and state or at least use religious rhetoric to mobilize the base, whether on the right or left. Some politicians have embraced forms of theocracy. That is a bit disturbing. Then there's the war in Ukraine, which pits two peoples who have deep roots in Orthodox Christianity. Both consider Kyiv (Kiev) and Crimea to be holy ground. So, which side represents God's will? I know who I back, but you can see the problem when church and state become entangled.

As noted above, the United States has enshrined in the Constitution a legal separation of church and

state, but religion and politics often intermingle. In fact, the so-called wall is often little more than a line in the sand. You may not have to be a

member of a specific religious community to hold office, but if you’re going to

run for political office it helps to be able to speak religion. Atheists need

not apply. As for religious institutions, they don’t receive official

government support for religious activities like evangelism, but there are tax

advantages that accrue. If you transgress certain rules you might you’re your tax

benefits, though this rarely happens.

So, while we may have a secular Constitution, religion always seems to

play a role in our political debates. In fact, politicians love to baptize Jesus

into their political party. Indeed, partisans left and right want to remake

Jesus in their own image. But is Jesus

open to being drafted as a political figure? Or, does he transcend our political

boundaries?

We seem

to be presented with a choice: Jesus the conservative or Jesus the progressive. But, the truth is Jesus isn’t a Democrat, a Republican, or a Democratic

Socialist. Those parties and ideologies didn’t exist in first-century

Palestine. While Jesus offered good news to the poor, he

was simply aligning himself with Jewish prophetic tradition (Luke 4:18-21). While

I do think Jesus had a preferential option for the poor and that there's a

political dimension to his message, we would be wise to refrain from making him

an honorary member of our political party. That doesn’t mean that being a

follower of Jesus shouldn’t have implications for the way we vote, but I don’t

think he’s a member of the party!

When I

preach on Palm Sunday, I try to keep in mind Good Friday. Whatever Jesus had

in mind when he put in his order for that colt, he ended up hanging on a Roman cross. Crosses aren't thrones. They served the Romans as a warning to would-be challengers to their political authority. They tried to send the message, but in the end, it failed. Even

as Palm Sunday doesn’t give us a full picture, neither does Good Friday. Easter

becomes the answer to both.

When we

read a passage like this, we need to understand that there were a variety of

views on matters of statecraft and religion in first-century Judaism. We also

need to remember that there was no such thing as a separation between religion

and statecraft. While Judaism didn’t see their rulers as divine beings, their

Roman overlords did, or at least they believed they were in special communion

with the gods. Nonetheless, we could say that first-century political systems

were theocracies. True secular states are a rather recent invention. The United

States was one of the first to separate church and state, but it left more room for religion to function in public than, let's say, France. So, when the people hailed Jesus as the king

who came in the name of the Lord, they weren’t just talking about religion. They were

also talking about politics. But Jesus’ politics wasn’t business as usual.

Jesus

seems to have provoked the reaction he got from the crowd. He was declaring

himself to be the sovereign ruler of Israel and perhaps more. At least in

Luke’s mind, Jesus seems to be more than simply another earthly ruler. He was

challenging the powers that be, both political and apparently religious. He did

so from within Judaism, but by the time Luke is writing the community has moved

beyond those boundaries. For Luke, Jesus is claiming sovereignty not only of

Israel but of the entire world. Such claims can’t go unanswered, so the cross is meant to stand in the way of Jesus' kingdom plans. Since we read this post-Easter, we can say that Jesus ultimately triumphed and that his realm transcends all political boundaries.

Comments