A Festival of Remembrance—Lectionary Reflection for Pentecost 15A/Proper 18A (Exodus 12)

Exodus 12:1-14 New Revised Standard Version Updated Edition

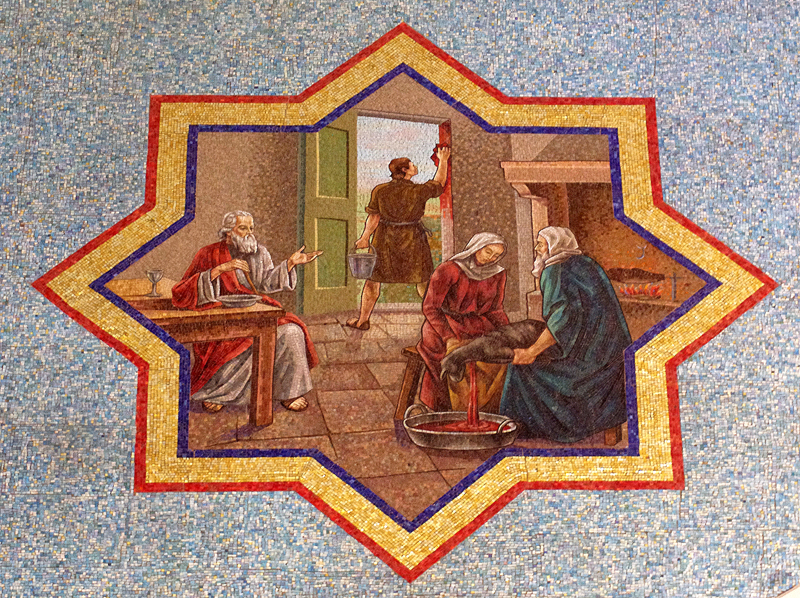

12 The Lord said to Moses and Aaron in the land of Egypt, 2 “This month shall mark for you the beginning of months; it shall be the first month of the year for you. 3 Tell the whole congregation of Israel that on the tenth of this month they are to take a lamb for each family, a lamb for each household. 4 If a household is too small for a whole lamb, it shall join its closest neighbor in obtaining one; the lamb shall be divided in proportion to the number of people who eat of it. 5 Your lamb shall be without blemish, a year-old male; you may take it from the sheep or from the goats. 6 You shall keep it until the fourteenth day of this month; then the whole assembled congregation of Israel shall slaughter it at twilight. 7 They shall take some of the blood and put it on the two doorposts and the lintel of the houses in which they eat it. 8 They shall eat the lamb that same night; they shall eat it roasted over the fire with unleavened bread and bitter herbs. 9 Do not eat any of it raw or boiled in water but roasted over the fire, with its head, legs, and inner organs. 10 You shall let none of it remain until the morning; anything that remains until the morning you shall burn with fire. 11 This is how you shall eat it: your loins girded, your sandals on your feet, and your staff in your hand, and you shall eat it hurriedly. It is the Passover of the Lord. 12 I will pass through the land of Egypt that night, and I will strike down every firstborn in the land of Egypt, from human to animal, and on all the gods of Egypt I will execute judgments: I am the Lord. 13 The blood shall be a sign for you on the houses where you live: when I see the blood, I will pass over you, and no plague shall destroy you when I strike the land of Egypt.

14 “This day shall be a day of remembrance for you. You shall celebrate it as a festival to the Lord; throughout your generations you shall observe it as a perpetual ordinance.

***************

The God

of Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob heard the cries of the Hebrews living in slavery

in Egypt. God appeared to Moses from the midst of a burning bush, commissioning

Moses to go to Pharaoh and liberate the people (Exod. 3:1-15). This is the same

Moses who was pulled from the Nile and adopted by Pharaoh’s daughter, and later

fled Egypt into the desert, where he took up the life of the shepherd (Exod.2). When Moses heard the call of God, he somewhat reluctantly agreed to go back

to Egypt and begin the process of liberating Israel. That process included ten

plagues, which finally got Pharaoh’s attention. We pick up the story in Exodus

12 after Pharaoh relented and agreed to Moses’ terms.

As the

people prepared to leave Egypt and head off to the Promised Land, Moses

revealed to them a festival that would mark the day of their liberation. It

would also mark the beginning of the year for Israel. In other words, this

would be the foundational story. This festival came to be known as Pesach or Passover,

and it continues to be celebrated by Jewish families and congregations to this

day. For as we read here in Exodus: “This day shall be a day of remembrance for

you. You shall celebrate it as a festival to the Lord; throughout your

generations you shall observe it as a perpetual ordinance” (Ex. 12:14).

After

receiving a word from God concerning their departure from Egypt, Moses and

Aaron instruct each family (or if the family is small to join with other

families) to find a yearling male lamb (either sheep or goat) that is without

blemish. The festival begins on the tenth day of the month and then on the

fourteenth day of the month, having watched over the lamb, the families (or groups

of families) are instructed to slaughter the lamb and divide it into appropriate

portions so that all might eat. They are then instructed to place the blood of

the lamb on the two doorposts and the lintel (top beam above the doorway) of

the house. Having placed the blood on their houses, they are instructed to eat

the meal that very night. They are to roast the lamb over fire, along with

unleavened bread and bitter herbs. God is quite specific—they are to roast the

lamb, not boil it in water or eat any of it raw. God wants to make sure nothing

goes to waste, so the head, legs, and entrails are included. Well, everything

but the blood. If anything is left over

the next morning, it’s to be burned. What we have before us is the foundation

for a seder, though not the seder as we would know it today. Rituals develop

over time!

The

meal described above is akin to a last supper. At least it’s the last supper to

be observed in Egypt. That’s because they are about to depart for parts

somewhat unknown. This Last Supper has connections to another Last Supper, the

one Jesus celebrated. For both meals and rituals were observed/established in a

context of oppression.

Moses and Aaron instruct people to

eat the meal with their loins girded, sandals on their feet, and their staff

close at hand. This will not be a leisurely dinner. They have permission to eat

quickly. But this is to be a Passover/Pesach offering to the LORD (Yahweh). In

other words, this is a protective offering, a sign for Yahweh to pass over the

house, as Yahweh goes about Egypt, killing the firstborn of Egypt. Not just human

firstborns, but animals as well. God is about to take revenge on Egypt and its

gods. God seals this command by self-identifying as “I the LORD” (Exod. 12:14 Tanakh).

This

final line of the reading is extremely challenging and problematic. It’s a bit

of the old “eye for an eye” form of judgment. It should be noted that in this

passage, God doesn’t seem to make a distinction between male and female. While

Pharaoh ordered the killing of Israel’s firstborn, he did so out of fear. He

also seemed unwilling to let the people go, even after numerous plagues. Perhaps

Pharaoh needed one more reminder that God stood with the Hebrews. Nevertheless,

it is a rather distressing message. We can take solace that is God who acts,

not the people of Israel. This is not a call for people to kill others, even if

this doesn’t sit well with a vision of God being love.

The

danger here is to get caught up in this word about God taking the lives of the firstborn

and concluding that this is another example of the Old Testament wrathful God,

who needs to be contrasted with the loving God of Jesus. In other words, we

must beware of our tendency to embrace Marcionism by distinguishing the God of

the Old Testament from the God of the New Testament, with one being wrathful

and the other loving. Perhaps we would be better served to follow the advice of

Ron Allen and Clark Williamson, who suggest we think of this account of the

killing of the firstborn (along with the entire plague scenario) as a

historical parable. This parable offers a lesson: “The fate of authoritarian

dictatorships hostile to freedom and well-being is always destruction” [Preaching the Old Testament, p. 84]. So as not to fall prey to Marcionism, Allen and

Williamson remind us that in both Testaments, God is associated with

destruction. But, as a parable with a message, they suggest we take from this the idea that “the alternative to God’s way of life and well-being (blessing) is death

and destruction and that our choice is between the two” [Preaching the Old

Testament, p. 85].

The

story of Passover continues through Exodus 13, so we have before us just the

opening paragraphs of a larger story that commemorates the primal story of the

nation of Israel. This story reminds the people of Israel that God does in fact

hear the cries of the oppressed and that God will deliver and redeem them. Barbara

Lundblad writes that “Exodus is a story of reversals, of slaves, set free and

the powerful thrown down. This story has sustained Jewish people through

pogroms and the holocaust. This story became the freedom song of African

American slaves in America” [Preaching God’s Transforming Justice, p.

382]. There is, of course, the shadow side to this story, as we’ve already

noted. Thus, she poses a good question for our reflection: “Can there be

freedom for some without destroying others?” (p. 382). Do acts of liberation

ultimately lead to the destruction or displacement of others? The story we have

before us doesn’t answer that question. Historically, movements of liberation

often find themselves turning to some form of violence to overcome injustice. While

we struggle with this word about the avenging God, we must not lose sight of

the revelation that the God of Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob is a liberating God. This

passage invites us to worship this God by celebrating God’s liberating action.

When it comes to the festival and

its meaning for us, Walter Brueggemann writes that the “verses provide an opportunity

to reflect on the cruciality of worship for the maintenance of the identity of

a historical community and on the importance of doing worship rightly”

[“Exodus,” New Interpreter’s Bible, 1:778]. He points out that our worship

experiences provide us with opportunities to tell the stories that define our

identity by connecting us to our primal past. That’s what happens here. They

are to remember this act of liberation in perpetuity on specific times/dates.

He also suggests that we avoid the temptation to over-explain. He notes that “much

Christian worship is either excessively doctrinal and rational or excessively

moralistic and didactic. In either case, it is excessively self-conscious.

Worship entails a willing suspension of disbelief, a reentering of a

definitional memory, and a readiness to submit to the memory as

identity-bestowing for parents and children [NIB, 1:778]. We needn’t

understand every element of the primal story to be formed by it. Regarding the

Passover experience, the rite/ritual carries the story. It involves the

slaughter of a lamb, the painting of doorposts, and a feast of roasted lamb.

It’s to be experienced with one’s shoes on and quickly because we need ready to

go when God is ready to lead. We might use this opportunity, as Christians, to

reflect on and remember our primal stories so that we’ll be ready to go when

God leads.

We must

remember, as Christians, that the passion narrative is built, at least in part,

on the Passover narrative. Consider Matthew’s version of the Last Supper. Jesus

and his followers gathered in the upper room to celebrate the Passover meal.

When Jesus shares the bread and cup with the community, he speaks of these

elements as signs of the blood of the covenant poured out for the forgiveness

of sins (a form of liberation) (Matt. 26:17-29). While Passover had nothing to

do with addressing Israel’s sin, like the cross, Passover, speaks of

liberation. In John’s Passion narrative, the connection of Jesus to the

Passover Lamb is even more explicit. John pictures Jesus being crucified on the

day when the Passover lambs are sacrificed in preparation for the feast (John19:14-30). Thus, for John, Jesus is the Passover Lamb, whose death provides for

liberation.

Our

calling as the people of God is to continually share the good news that the God

we worship and serve is a liberating God. As we share this good news, we can

invite others to share in this act of divine liberation.

Comments