A Reluctant Preacher & A Merciful God—Lectionary Reflection for Epiphany 3B (Jonah 3:1-5, 10)

Jonah 3 New Revised Standard Version Updated Edition

3 The word of the Lord came to Jonah a second time, saying, 2 “Get up, go to Nineveh, that great city, and proclaim to it the message that I tell you.” 3 So Jonah set out and went to Nineveh, according to the word of the Lord. Now Nineveh was an exceedingly large city, a three days’ walk across. 4 Jonah began to go into the city, going a day’s walk. And he cried out, “Forty days more, and Nineveh shall be overthrown!” 5 And the people of Nineveh believed God; they proclaimed a fast, and everyone, great and small, put on sackcloth.

6 When the news reached the king of Nineveh, he rose from his throne, removed his robe, covered himself with sackcloth, and sat in ashes. 7 Then he had a proclamation made in Nineveh: “By the decree of the king and his nobles: No human or animal, no herd or flock, shall taste anything. They shall not feed, nor shall they drink water. 8 Humans and animals shall be covered with sackcloth, and they shall cry mightily to God. All shall turn from their evil ways and from the violence that is in their hands. 9 Who knows? God may relent and change his mind; he may turn from his fierce anger, so that we do not perish.”

10 When God saw what they did, how they turned from their evil ways, God changed his mind about the calamity that he had said he would bring upon them, and he did not do it.

**************

There

was a preacher named Jonah whom God called upon to deliver a message of

judgment on a hated enemy—the Assyrian Empire pictured here as Nineveh. Jonah at first ran away when the call came. He

was no Isaiah, who responded to God’s call with open arms, declaring: Here I

am, send me” (Is. 6:8). You may remember that Jonah headed out to sea. After a

storm threatened to destroy the boat, he ended up being thrown into the sea and

ended up in the belly of a great fish (or whale depending on the way you want

to tell the story). Why did Jonah run away? He wanted to have nothing to do

with Nineveh. Whatever God wanted to do with them God could do without him. There

was no need for Jonah to give Nineveh the opportunity to repent. Nevertheless,

while you can run from God you can’t hide, and so here we are in chapter 3 of

Jonah. Once again God calls on Jonah to go to Nineveh and preach. It appears he

learned his lesson because he headed off to Nineveh.

Now we need to get something

straight from the beginning. We’ll miss the point of the story if we try to

historicize it. If we try to do so, problems begin with the three days in the

belly of the fish (Jonah 1:17). So maybe we dispense arguing about such things

and think in terms of a fable or even a parable, a story that has a purpose

behind it. So, to get a sense of things, let’s start with Nineveh, which was at

one time the capital of the Assyrian Empire, an empire known for its oppressive

cruelty when it came to conquered territories. Think here of the northern kingdom

of Israel that essentially disappeared after the Assyrian conquest. The reader

would begin with a certain disdain for the object of the story. So, we’re being

set up (as was Jonah) for a surprise ending that might go against the grain.

When it comes to Jonah, he had no

interest in going to Nineveh. It was a foreign territory that didn’t deserve to

hear a word from God. When Jonah reluctantly arrived in Nineveh (the historical

city of Nineveh lay in the northern reaches of what is now Iraq), he began his

journey through the city. The author tells us it was a rather large city that

took three days to cross (walking). The message he delivers is quite simple: “Forty

days more, and Nineveh shall be overthrown!” Jonah didn’t say why Nineveh

would be overthrown or by whom. No mention is made here of Yahweh. There is no

call for repentance and no offer of mercy is made available. There’s no

ambiguity in the message. It’s just doom and gloom.

When the Ninevites hear this

message, they do the unexpected. They believe the message and repent. Not only

that but they proclaimed a fast and everyone from the greatest to the smallest

put on sackcloth, a traditional sign of lament, mourning, and repentance. No

mention of ashes is made, but perhaps that is assumed. Not only did all the

people respond positively to the message, but so did the king. Now, the

lectionary omits verses six through nine, which take note of the king’s response,

including the issuance of a decree calling on everybody in the city to fast and

put on sackcloth. Not only should the people do this, but he decreed that animals

should fast and have sackcloth placed on them. Could this be why Jonah wanted to run away? Could

Jonah have anticipated a successful revival, and he didn’t want to see it

happen, at least not with his participation?

The question that continually gets

raised when it comes to the story of Jonah is its purpose. If this is not a historical

account of a great revival, and there is no evidence that the people of Nineveh

ever rejected their gods or abandoned their oppressive ways, then what does the

author want to communicate about Jonah and Yahweh?

Let’s start with Jonah. He appears

to be a rather narrow-minded nationalist. Of course, depending on when this was

written, the reader/listener likely knew of how the Assyrians dealt with Israel.

These are nasty people who pick on nations much smaller than them. Surely, they

deserve whatever God might deal to them. But Jonah also represents what we

might call a xenophobe. He hates or at least views foreigners with disdain, at

least the ones who live in Nineveh. You know, he might have had good reason

based on the Assyrian reputation as one of history’s most brutal empires. So,

negative feelings are expected.

The problem the text poses is that the

people repented, including the king. That is because they believed the message

Jonah preached and responded by demonstrating a change of heart. From the perspective of Jonah, that was bad

news. He wanted Nineveh to be destroyed. But, as the omitted section of the

chapter reveals, the king pondered the question: “Who knows? God may relent and

change his mind; he may turn from his fierce anger, so that we do not perish”

(Jonah 3:9). That “who knows?” question is an important one. Jonah didn’t give

any hope that God would relent. It’s clear that Jonah hoped God wouldn’t

relent. But, the king held on to the possibility that God might be gracious if

the people, and even the animals, showed signs of repentance. If that was true,

then perhaps they might not perish.

Jonah’s worst possible outcome

occurred. Just as the king hoped God would relent, as verse ten reveals, God

did have a change of heart. Yes: “When God saw what they did, how they turned

from their evil ways, God changed his mind about the calamity that he had said

he would bring upon them, and he did not do it.” That’s what Jonah was really

afraid might happen. Here’s the question this book raises, especially for those

who believe that God is, to use a philosophical term, “immutable”

(unchangeable) and “impassible” (without feelings). What we see here is that

God can change and that is due to God’s mercy. Or might we say God’s steadfast

love?

Now there is more to this story. We

end with God’s change of heart such that Nineveh is spared. What we don’t get

is Jonah’s response, which is found in chapter 4 of Jonah. In the final chapter of this

story, Jonah sulks because God failed to destroy Nineveh. He kind of feels like

a fool. Here he had spent three days walking through Nineveh telling the people

that within forty days they would be as good as dead. But then God responded to

their response with mercy. That’s not what he wanted. Now if we turn the page

and go to chapter 4, we read about Jonah’s anger, first that Nineveh was spared

and then that the bush that he was sitting under shriveled up, so he no longer

had shade from the burning sun. As he pouted, he told God it would have been better

for him if he had died. That’s because he knew that God is ”a gracious and

merciful God, slow to anger, abounding in steadfast love, and relenting from

punishment” (Jonah

4:2).

I think it’s worth hearing God’s

response to Jonah’s anger about the “death” of the bush.

Then the Lord said, “You are concerned about the bush, for which you did not labor and which you did not grow; it came into being in a night and perished in a night. 11 And should I not be concerned about Nineveh, that great city, in which there are more than a hundred and twenty thousand persons who do not know their right hand from their left and also many animals?” (Jonah 4:9-11).

Jonah is concerned about a bush that grew up and perished

without any labor on Jonah’s part. So why shouldn’t God be concerned about the

people and the animals who seem lost (don’t know their right hand from their

left)? Why shouldn’t God show them mercy? That’s the question the author leaves

us with.

We live

in an age of great polarization. People in the United States, my country, have

divided into rival teams. We perceive each other as enemies. When it comes to

the rest of the world, well they don’t seem to matter either. We watch as war

destroys and kills in places like Ukraine and the Middle East. There are wars

in places we ignore. People are experiencing great poverty and oppression. My

life is pretty serene, but that’s not true for all. So what message might the

story of Jonah offer us? How might its message of divine forgiveness overcome

our Jonah-like response to the rest of the world? When I read this passage, I see a person who

is clearly ethnocentric. He would fit well with the isolationist and

anti-immigrant crowds. Fear of foreigners is driving politics across the globe.

We see it here in the United States, but it’s running rampant throughout Europe,

as anti-immigrant parties gain power in places like Hungary and even the

Netherlands. As we read the news and see the world as it is, what word might

the story of Jonah offer us?

Could it be that God is concerned

about those other people as well as you and me?

Might this story open our eyes to God’s grace and mercy, not just for

others but for us as well? Yes, maybe we need to repent and seek forgiveness

for the hardness of our own hearts. While Jonah, the very reluctant prophet, was upset that God didn’t

destroy Nineveh, he reveals something important about God when he says: “I knew

that you are a gracious and merciful God, slow to anger, abounding in steadfast

love, and relenting from punishment” (Jonah 4:2). Isn’t that good news, not

just for others, but for us as well?

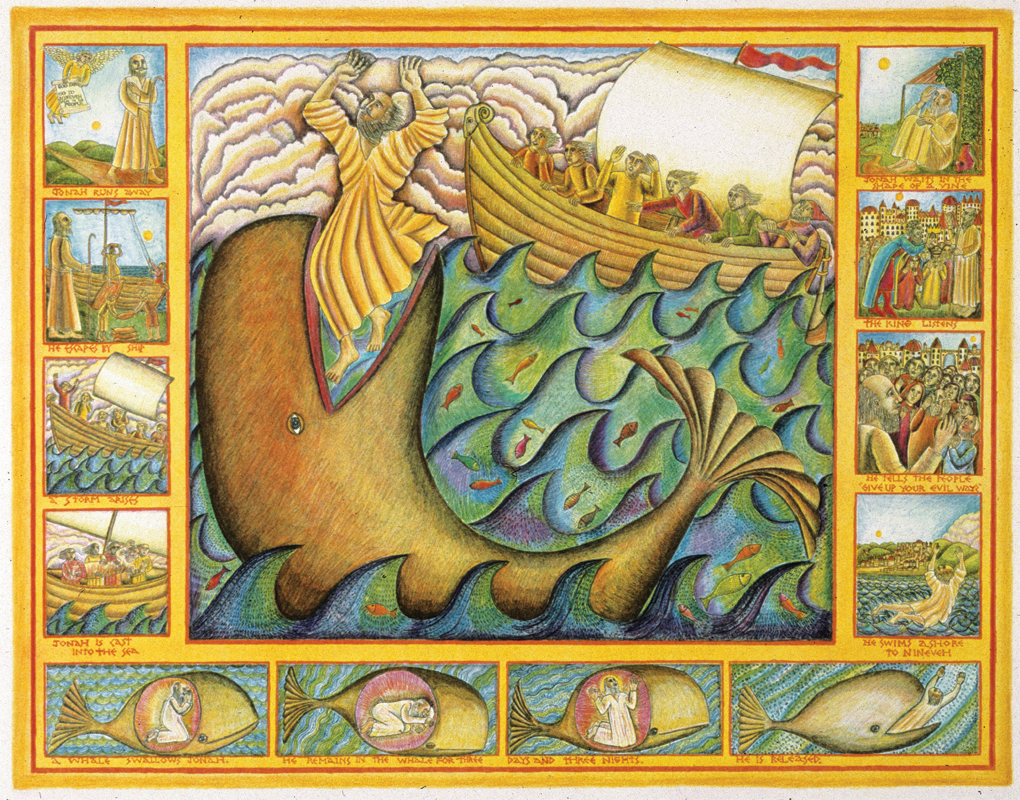

Image Attribution: Swanson, John August. Jonah, from Art in the Christian Tradition, a project of the Vanderbilt Divinity Library, Nashville, TN. https://diglib.library.vanderbilt.edu/act-imagelink.pl?RC=56549 [retrieved January 11, 2024]. Original source: Estate of John August Swanson, https://www.johnaugustswanson.com/.

Comments