Healing Faith -- Lectionary Reflection for Pentecost 15B (Mark 7:24-37)

24 From there he set out and went away to the region of Tyre. He entered a house and did not want anyone to know he was there. Yet he could not escape notice, 25 but a woman whose little daughter had an unclean spirit immediately heard about him, and she came and bowed down at his feet. 26 Now the woman was a Gentile, of Syrophoenician origin. She begged him to cast the demon out of her daughter. 27 He said to her, “Let the children be fed first, for it is not fair to take the children’s food and throw it to the dogs.”28 But she answered him, “Sir, even the dogs under the table eat the children’s crumbs.” 29 Then he said to her, “For saying that, you may go—the demon has left your daughter.” 30 So she went home, found the child lying on the bed, and the demon gone.

31 Then he returned from the region of Tyre, and went by way of Sidon towards the Sea of Galilee, in the region of the Decapolis. 32 They brought to him a deaf man who had an impediment in his speech; and they begged him to lay his hand on him. 33 He took him aside in private, away from the crowd, and put his fingers into his ears, and he spat and touched his tongue. 34 Then looking up to heaven, he sighed and said to him, “Ephphatha,” that is, “Be opened.” 35 And immediately his ears were opened, his tongue was released, and he spoke plainly. 36 Then Jesus ordered them to tell no one; but the more he ordered them, the more zealously they proclaimed it. 37 They were astounded beyond measure, saying, “He has done everything well; he even makes the deaf to hear and the mute to speak.”

*****

Healing stood at the center of Jesus’ ministry. Wherever he went he ended up healing people. He was, you might say, a healing evangelist. In many ways, Jesus’ healing ministry is scandalous, at least for more progressive/modernist Christians. More preferable is a demythologized Jesus, one who is more community organizer than a miracle worker. Standing at the heart of the issue is the problem of miracles and whether ours is an interventionist God. One of the problems presented by an interventionist understanding of God is that God is essentially a gap-filler. On the other hand, why bother with a God who isn’t present nor active in our world and in our lives. An absent/distant God is of little use. Besides, the stories of Jesus the healer remain strongly present in the Gospels (which might explain why some progressives prefer Thomas or Q, since that Jesus is just a talking head who never really does much). If we take the healing portions out of the Gospels (something that Thomas Jefferson famously did), we would seem to lose something important. Jesus’ actions often provide the foundation for his teachings. Without them the teaching moments are disembodied.

What we see and hear in the stories of Jesus’ healing experiences is an expression of divine compassion and grace. Jesus’ healing actions are all expressions of the work of the Holy Spirit and have eschatological significance (Luke 4:18-19). That is, they are signs of the inbreaking of the realm of God. Theologian Amos Yong suggests that “the life, ministry, death, and resurrection of Jesus are pneumatologically constituted events that signify the coming era, proleptically announcing and providing a foretaste, in the past (and present), of the eschatological future of God” [The Spirit of Creation: Modern Science and Divine Action in the Pentecostal-Charismatic Imagination (Pentecostal Manifestos), p. 90]. I would take this to mean that even as Jesus brings wholeness to bodies and minds, he is living out the vision of God for the world. The problem, however, remains that God seems to be tampering with divinely laid out laws of nature. The vision present in the Gospels is of a God who doesn’t seem to be bound by such rules. One way to get around a mechanistic vision is to appeal to quantum physics, a topic that is deeper and more complex than we have time or space to explore. So, perhaps we’re not left with a choice between supernaturalism and a Humeian vision of miracles as transgressors of natural laws. But that is a conversation for another day.

In the reading from Mark 7, Jesus the healer appears, but he appears in rather unusual contexts that offer another set of challenges to our understandings of Jesus’ identity. There are two healing stories present in the readings. Both events occur in predominantly Gentile contexts. In the previous section of the Gospel, Jesus has challenged the traditions of the elders. He has redefined what is clean and unclean. It is a matter of the heart, not external observances that constitute faithfulness to God. Now, having set out this standard Mark has Jesus venture into predominantly Gentile territory. Tyre is a city on the coast traditionally linked to the Phoenicians. The second healing takes place in the Decapolis, a Gentile region east of the Sea of Galilee. Could the first healing encounter have triggered the second?

If you are like me you envision Jesus as an open/welcoming person. His is an inclusive vision that is rooted in the Jewish vision of God’s desire to bless the nations. It is only natural for him to treat Gentiles in the same way he treats fellow Jews. But in this passage, we discover a side of Jesus we forget is there. It is a reminder that we all have a tendency toward ethnocentrism, at least until we have something like a conversion experience. That’s what happens at Tyre.

Jesus has gone to this heavily Gentile city for some undisclosed reason. I’m assuming that he stays at the home of a fellow Jew who happens to live there. Most metropolitan cities had a Jewish community of some sort. Who this person was isn’t revealed to us. Mark tells us that Jesus didn’t want anyone to know he was there (the Markan Jesus is keen on keeping a low profile, though it never works out that way). This woman, a Gentile of Syrophoenician background, somehow gets wind of Jesus' presence in the community. How this happens, again we’re not told. She comes to the house and begs Jesus to cast a demon out of her daughter.

It is at the point of the woman begging Jesus to heal her daughter that ethnocentrism emerges. Jesus tells the woman that it’s not appropriate for the children’s food to be thrown to the dogs (calling one a dog has long been a derogatory term—and contextually they might not have been humanity’s best friend). The woman, however, remains undaunted. Jesus has just insulted her. He has essentially told her to get off his grass, but that makes no difference to her. She accepts his abuse and continues to pursue his intervention in the life of her daughter. She’s desperate, and desperate times require desperate measures. She tells Jesus that even the dogs eat the scraps that fall to the floor. That’s all she’s asking for—just the scraps from the table. Jesus responds to her forceful response by extending healing grace to her daughter. He tells her to go home and find her child healed.

What should we make of this passage? What message do we hear in it? It certainly raises questions about Jesus’ own vision. Perhaps he needs to be converted as well. It should be noted that in Mark 5 Jesus healed the Gerasene demoniac, which was a Gentile area as seen by the presence of the swineherd (Mark 5:1-20). So, why did he respond like he did? Could it be that it was her gender and that her request had not been made by a man? It’s possible. Whatever the case, the woman’s persistence leads to a change in Jesus’ own understanding of his calling. Could it be that Jesus is faced with the question of his own hypocrisy, which he had earlier challenged (Mark 7:1-23)? In other words, does Jesus face the reality of being fully human? This encounter helps Jesus come to a broader vision of his ministry, one that is truly inclusive and open. Without her intervention would this have happened?

The healing of the woman’s daughter is followed by the healing of a deaf man in the Decapolis (one city in that region being Gerasa, where Jesus had earlier healed the demoniac). Fresh off this encounter with the woman at Tyre Jesus finds himself in another Gentile region. No longer is he showing off his ethnocentrism. When the friends of the man who is deaf approach him and ask that he heal him, Jesus responds without hesitation. He takes him aside and heals him. He does so with a specific prophetic ritual—putting his fingers in the man’s ears and spitting and then touching the man’s tongue, declaring “Ephphatha” or “be opened.” The man responds by speaking plainly. And then in true Markan fashion, Jesus tells the man and his friends to keep silent about what has transpired. Of course, as always occurs, they don’t obey. They go and tell their story. How could they not? Something life-changing had happened. You have to share that word.

Loye Bradley Ashton suggests that what we have here is an “Ephphatha Christology.” Noting that the experience with the Syrophoenician woman revealed the true extent of Jesus’ humanity, she writes: Jesus is fully God and fully human only if he can faithfully ‘be opened’ to both at the same time” (Feasting on the Word: Year B, Vol. 4, p. 48). Having been opened to a wider vision through this conversion experience, Jesus is ready to truly live out an inclusive vision of the Gospel. Going back to the encounter with the Syrophoenician woman, it is appropriate to remember the image of the bread. Meals in the ancient world were expressions of social boundaries. You ate with those like you. Jesus’ own table fellowship tended to break down boundaries. This encounter helps move Jesus toward that inclusive vision that they too are called to embrace. As Paul declared to the Galatians—“there is no longer Jew or Greek, there is no longer slave or free, there is no longer male and female; for all of you are one in Christ Jesus” (Galatians 3:28). This is the greatest miracle, and one to be greeted with joy, that that the boundaries we set are removed and humanity experiences true healing.

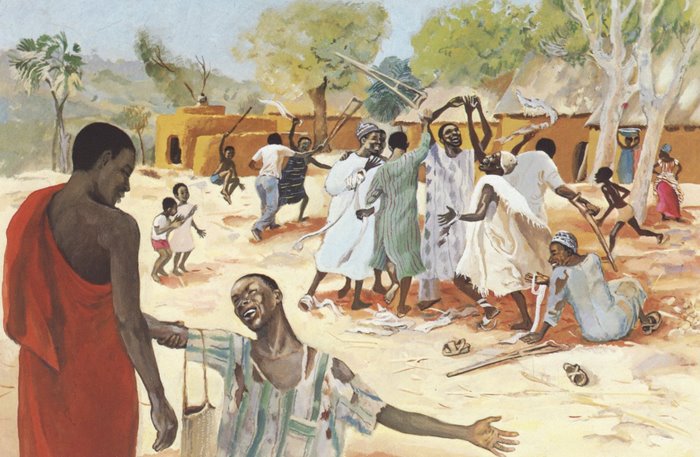

Image Attribution: JESUS MAFA. Healing of the ten lepers, from Art in the Christian Tradition, a project of the Vanderbilt Divinity Library, Nashville, TN. https://diglib.library.vanderbilt.edu/act-imagelink.pl?RC=48295 [retrieved August 28, 2021]. Original source: http://www.librairie-emmanuel.fr (contact page: https://www.librairie-emmanuel.fr/contact).

Comments