Mediator of a New Covenant - Lectionary Reflection for Pentecost 23B (Hebrews 9)

Hebrews 9:11-15 New Revised Standard Version

11 But when Christ came as a high priest of the good things that have come, then through the greater and perfect tent (not made with hands, that is, not of this creation), 12 he entered once for all into the Holy Place, not with the blood of goats and calves, but with his own blood, thus obtaining eternal redemption. 13 For if the blood of goats and bulls, with the sprinkling of the ashes of a heifer, sanctifies those who have been defiled so that their flesh is purified, 14 how much more will the blood of Christ, who through the eternal Spirit offered himself without blemish to God, purify our conscience from dead works to worship the living God!

15 For this reason he is the mediator of a new covenant, so that those who are called may receive the promised eternal inheritance, because a death has occurred that redeems them from the transgressions under the first covenant.

*******************

The

overarching message of the Book of Hebrews is that Christ is both our perfect

high priest and the perfect sacrifice. The calling of this high priest is

rooted in the priesthood of the mysterious Melchizedek. This has been a major

point of discussion in the previous two lectionary readings (Revised Common

Lectionary). As we’ve seen, the danger here is that when Hebrews speaks of the

priesthood of Jesus and a new covenant supersessionism creeps in. That is, Christianity

is understood as replacing Judaism as God’s covenant people because the covenant

Jesus initiates is a better covenant. That has had horrific consequences down

through the ages.

With

the danger of supersessionism in mind, we can attend to the message of Hebrews

that speaks of the difference between old and new covenants. As I’ve noted in

an earlier reflection the contrast doesn’t have to be between Judaism and

Christianity, with Christianity replacing Judaism. Rather, Hebrews seems to

have a different vision, one that contrasts the earthly and the heavenly. Now

the sacrificial/priestly system of ancient Israel does provide the model for

the earthly side of the equation, but the interpretive grid here is Platonism. We’ve

already established that the author is steeped in some form of Platonism. Therefore,

it’s not surprising that there are similarities between what we read in Hebrews

and the writings of the Alexandrian Jewish philosopher Philo.

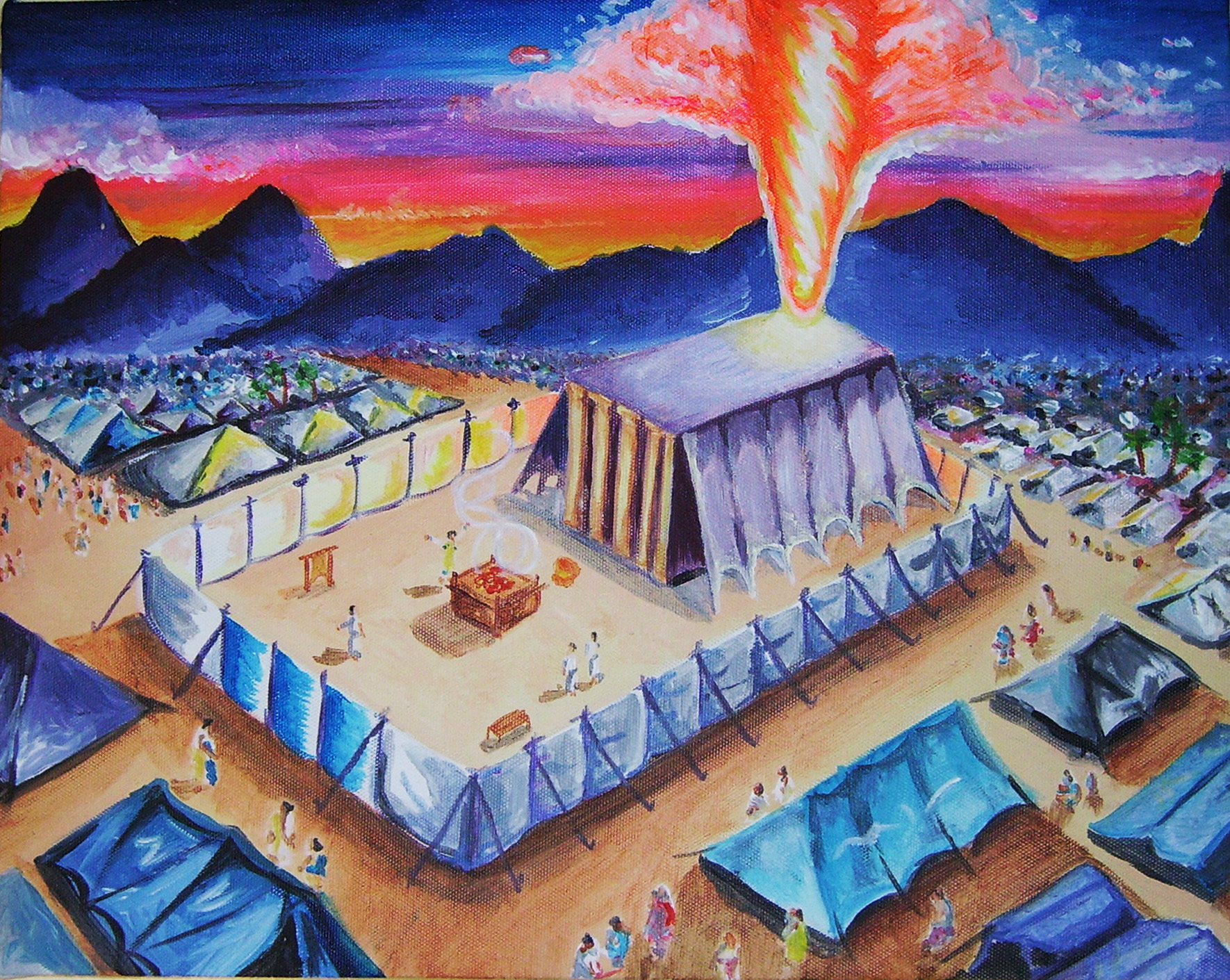

As we

come to this reading from Hebrews 9, we are again told that Jesus is our high

priest and that in this role he brings good things to us. While he holds this

position, it is interesting that the author doesn’t speak of the Temple in

Jerusalem. Instead, the author takes us back to the Book of Exodus and the tent

or Tabernacle. Whether or not the author of Hebrews knows the Gospel of John,

the reference to the tent here does bring to mind the message of John 1:14,

that the Word (Logos) of God became flesh and dwelt (tabernacled) among us.

Whether

or not the Jerusalem Temple still stands when this is written doesn’t seem to

matter to the author who takes us further back to that mobile worship space. Thus,

Jesus doesn’t enter the Temple. Instead, he enters the Tabernacle where he

performs the priestly duties. This tent is not made by human hands. It is not

of this creation, which suggests this is a heavenly tent, not an earthly one.

That should be a clue to what is going on here. The author’s Platonism seems to

be at work here. The earthly tent/temple is a shadow of the heavenly

tent/temple. This heavenly tent is where Jesus does his priestly work.

Not

only does Jesus act as priest in this perfect, that is heavenly, tabernacle,

but he also offers himself as the sacrifice that brings redemption. Standing

behind all of this is the Day of Atonement, the one day of the year when the

priest entered the Holy of Holies and offered sacrifices of redemption. This annual event stands as a shadow or

analogy for what Jesus does as both priest and sacrifice.

If we

go back to the beginning of the chapter, which is omitted in this reading

designated by the Revised Common Lectionary, we read:

Since the law has only a shadow of the good things to come and not the true form of these realities, it can never, by the same sacrifices that are continually offered year after year, make perfect those who approach. 2 Otherwise, would they not have ceased being offered, since the worshipers, cleansed once for all, would no longer have any consciousness of sin? (Heb. 9:1-2).

Note how Hebrews speaks of the law being “a shadow of the

good things to come” but it is “not the true form of these realities.” This is

Platonism at work. The earthly is the archetype or shadow of the true and

perfect heavenly form. As we sometimes say of Platonism that which is in heaven

is “the really real.” What Jesus does on the cross is enter the heavenly

Tabernacle and perform the priestly duties, which the Jewish priests perform as

a way of prefiguring what happens in heaven.

So, when

it comes to the Temple/Tabernacle sacrifices offered by the Levitical priests,

it’s not a question of effectiveness. The blood of goats and bulls does

sanctify and purify the flesh of those who are defiled, but the blood of Jesus

goes further. As we read through Hebrews, it’s important to remember that in

the ancient world animal sacrifices were a regular part of life, in Israel and

its neighbors. It’s just the way things were—in fact, that’s one of the

concerns of I Corinthians, should one eat meat from the pagan sacrifices?

In any

case, when it comes to the blood of Jesus, which is offered without blemish,

through the Spirit, purifies the conscience from dead works. While the cross

may be in view here, it is not mentioned. What is important to the author is

that the ones who are purified of dead works through this act Jesus’ part can now

worship the living God. As for the identity of these dead works, Ron Allen and

Clark Williamson helpfully note that “the ‘dead works’ should not be confused

with the mitzvoth of torah. ‘Dead’ works are not ‘deeds of loving

kindness’; they are sins that pollute the conscience” (Preaching the Letters without Dismissing the Law, p. 43].

Having defined how

Jesus acts as both priest and sacrifice so that in doing so our consciences

are purified and we’re now able to worship God with clean consciences, Hebrews

moves on to Jesus’ role as “mediator of a new covenant” (v. 15). The reading

designated by the Revised Common Lectionary ends in verse 15, though the nature

of this covenant and how it is implemented is described in the rest of the

paragraph. This covenant, we’re told, requires blood, as is true of all

covenants. So, just Jesus’ blood purifies, it becomes the foundation for a new

covenant. The idea of a new covenant is rooted in Jeremiah 31, where we are

told the new covenant will be written not on stone but on our hearts. Since the

reading ends with verse 15 and doesn’t go further, we are simply told that this

new covenant that Jeremiah promised is mediated to us by Christ. What is said

here is a restating of the earlier declaration in Hebrews 8:6, that Jesus “is

the mediator of a better covenant, which has been enacted through better

promises.” This is where things get tricky. The question is: if God made the

first covenant with Israel, why would God need to redo things? Nevertheless,

here in chapter 9, the message of the new covenant is that with the new

covenant comes the “promised eternal inheritance.” It would seem that the key

is the death of Jesus, which “has occurred that redeems them from the

transgressions under the first covenant.” For Hebrews the difference appears to

be that the offering made Jesus is made once for all, offering the ransom that

redeems. Therefore, we receive the eternal inheritance.

As we ponder this word about Jesus’ offering of himself to God fully, we can read this not only in light of the cross, which is never mentioned here, but in terms of his act of worship of God. Fred Craddock writes:

Christ’s offering of his life to God was the ultimate act of worship in order that we, with purified consciences, may "worship the living God." What, then, is this worship if it is not the offering of ourselves to God in ways appropriate to the nature of God and the needs that present themselves to us? On this matter, the word of Hebrews is not unlike the urging of Paul to the Roman Christians: "present your bodies as a living sacrifice, holy and acceptable to God, which is your spiritual worship" (Rom. 12:1 NRSV). [“Hebrews," New Interpreter’s Bible, 12:118].

Thus, Hebrews invites us to participate in the work of Christ by

sharing in the worship of God and all that this entails.

Comments