Apostolic Hands - Lectionary Reflection for Baptism of Jesus Sunday/Epiphany 1C (Acts 8)

Acts 8:14-17 New Revised Standard Version

14 Now when the apostles at Jerusalem heard that Samaria had accepted the word of God, they sent Peter and John to them. 15 The two went down and prayed for them that they might receive the Holy Spirit 16 (for as yet the Spirit had not come upon any of them; they had only been baptized in the name of the Lord Jesus). 17 Then Peter and John laid their hands on them, and they received the Holy Spirit.

***************

It is

Baptism of Jesus Sunday. This first Sunday after Epiphany offers us an

opportunity to reflect on Jesus’ baptism, as well as the role baptism plays in

the early church and our own lives. It is safe to say that the sacrament of

baptism, like Holy Communion, is a contested point in the life of the church. In

other words, we’re not all on the same page when it comes to form and meaning.

The churches have different theologies and practices, which can prove divisive.

Some churches practice infant baptism and others do not. Some immerse and

others don’t. For some baptism is a necessary step in the process of salvation.

For others, it is a sacramental act that washes away original sin. It can be

understood as the Christian version of circumcision, and thus is a covenant

marker. It could also be seen as that point at which the Spirit is received by

a believer. In other words, there is more than one option when it comes to

understanding baptism. So, what is your theology and practice of baptism? That

is, what is your story when it comes to baptism.

A point

of confession is appropriate here. I’m ordained in a denomination that

practices believer baptism by immersion. At one time my denomination held so

tightly to this position that some in the movement insisted that if you weren’t

immersed on the profession of faith (for the remission of sins) then you’re not

a Christian. Alexander Campbell one of our founders had to pen a response to

questioners concerning the fate of the “pious unimmersed.” The good news is

that he admitted that though deficient in form, they were nonetheless part of

the family. However, if you wanted to be a member of the church, then you would

need to be immersed. Disciples now practice “open membership” and don’t

rebaptize, but we still immerse. While that is the denomination of my ordination,

I was baptized as an infant and confirmed at the age of twelve in the Episcopal

Church. But, when I was in high school, I decided that this earlier baptism was

insufficient, so I was immersed in a creek at camp upon profession of faith. Even

that was not sufficient, or so I thought, so eventually, I followed the lead of

my Pentecostal context and was baptized in the Spirit with the initial evidence

of speaking in tongues. So, whatever the requirements for getting into the

kingdom of God, I believe I’ve met them. What I can say is that baptism is

important to me. It is the seal and sign that as a follower of Jesus the Spirit

of God inhabits my life.

We can

find a number of texts that speak directly or indirectly to baptism. The Gospel

reading for Baptism of Jesus Sunday in Year C comes from Luke 3, while the

Second Reading (normally coming from the Epistles) draws from a story in the

Book of Acts. When we look to the New Testament, things can appear unclear when

it comes to the timing of baptism and whether anything else is required. Thus,

we have fodder for different theologies and practices. While in Matthew the

Apostles are commanded to baptize in the Name of the Father, Son, and Holy

Spirit (Mt. 28:19), in Acts baptism in the name of Jesus is sufficient. In

fact, the book of Acts offers a fairly forward formula for anyone wanting to be

saved. On the Day of Pentecost, after Peter finishes his sermon, he responds to

the question of what must be done to be saved by calling on the people to “Repent,

and be baptized every one of you in the name of Jesus Christ so that your sins

may be forgiven; and you will receive the gift of the Holy Spirit” (Acts 2:38).

That seems rather straightforward. What more could we ask?

Well,

things get more complicated here in chapter 8 of the Book of Acts. We meet up

with Philip the Evangelist, one of the Seven, who goes to Samaria and preaches

and then meets up with an Ethiopian official. Before we get to the situation in

Samaria, I want to take note of the encounter with the Ethiopian. According to

the Book of Acts, Philip is plopped down next to the chariot in which the

Ethiopian is riding while reading from Isaiah. After Philip explains the

passage in terms of the message of Jesus, the Ethiopian asks what prevents him

from being baptized. Seeing nothing, they go down into a pool of water and

Philip baptizes him. Then, off went the Ethiopian (Acts 8:26-38). That suggests

that if somebody wants to be baptized, go for it!

That

leads us back to the preceding story in Acts 8. We learn that Philip the

Evangelist had fled Jerusalem after the martyrdom of Stephen. When he entered

the region of Samaria, he began to preach about Jesus the Messiah (remember

Jesus’ instructions in Acts 1:8—the gospel was to be proclaimed in Jerusalem

and then in Judea and Samaria, and Philip fulfills this set of

instructions). We’re told that even as he preached, Philip’s message was accompanied

by signs and wonders. All of this caught the attention of members of the

Samaritan community who responded positively and received baptism from him. I’m assuming that Philip followed the script

laid out by Peter, so we can assume the people repented, were baptized, and had

received forgiveness of sins. However, it appears they were lacking one thing.

That was the Holy Spirit. So, why didn’t they receive the Holy Spirit when they

were baptized? What was the hitch in this otherwise straightforward process? That

question has led to many theories and solutions.

Whatever

the reason for this lack, and there are several possible reasons why things

place this way, the Apostles in Jerusalem heard about the revival in Samaria.

So they sent Peter and John to investigate. When the two apostles arrived, they

laid their hands upon the people and prayed for those who had been baptized

that they might receive the Holy Spirit. The reason for this was, as Luke tells

us, the Samaritan believers had only been baptized in the name of Jesus. While

following the reading from Acts 2 that should have been enough, apparently it

wasn’t. So, why the presence of the Apostles?

In my

Episcopalian days, I learned that while priests and deacons baptized, bishops

laid hands on candidates confirming them in the faith. Thus, at that point, believers

received the Holy Spirit through the episcopal actions. You can see why this

served as justification for the rite of confirmation, which in the Episcopal

Church is not a sacrament but completes the actions begun in baptism.

While

that explanation helps support the rite of confirmation, I’m not sure that is what

Luke has in mind here. An answer that has long made sense to me has to do with

border crossings. Up to this point, all those who had responded (at least in

the Book of Acts) to the Gospel message were Jews. To this point, the Jesus

community was essentially a sect of Judaism. This would be the first border

crossing. While Samaritans and Jews were related, they were separated from each

other doctrinally and culturally. They didn’t like each other. So, perhaps, a second

step was necessary to cement the relationship between the two communities in

Christ. What better way to cement the relationship than apostolic participation

in welcoming these new believers into the church. Since, in the Book of Acts,

the Spirit is the one who guides and empowers the expansion of the community, withholding

the Spirit until there was apostolic confirmation was a fruitful way of

bringing the two together.

What

the passage does here is offer us another opportunity to reflect on the nature

of baptism. What does it accomplish? What is the relationship of baptism to the

Holy Spirit? Acts 2 suggests they belong together. Here baptism and the

reception of the Holy Spirit are separate events. Later in Acts 10, the Spirit

falls on a group of Gentiles even before they are baptized, which leads Peter

to ask the question: if God baptizes with the Spirit, then how can water then

be held back? Even later in Acts, Paul encounters a group of Jesus followers

who had received John’s baptism but didn’t know anything about the Holy Spirit,

so Paul had them all rebaptized in the name of Jesus. At that point, the Holy

Spirit came upon them, and they spoke in tongues and prophesied (Acts 19:1-7). So

perhaps what Acts does is connect the Spirit with baptism, but different

contexts require different responses. Willie James Jennings, in his comments on

the reading from Acts 19 notes that “the saving work of God is always new,

always starting up and again with faith. . .. Here we see the Spirit’s tendency

and technique. The Spirit lovingly joins the caressing of our skin through the

water and the laying on of hands. Both the water and the touch become the stage

on which the Spirit will fall on our bodies, covering us with creating and

creative power and joining us to the life of the Son. Through the Spirit, the

word comes to skin, and becomes skin, our skin in concert with the Spirit” [Acts: Belief, pp. 184-185].

The

timing may differ from one context to the next, but the good news is that in

baptism we are encompassed by the Spirit of God in Christ and that it bridges

differences, creating a new community of the Beloved.

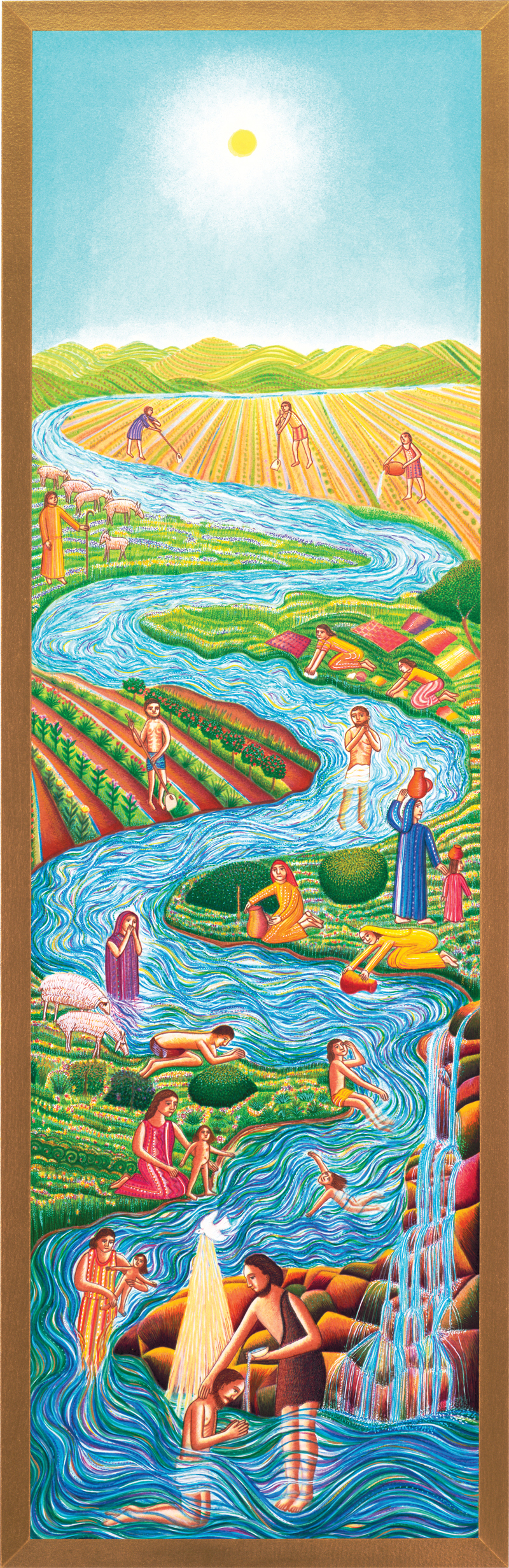

Image Attribution: Swanson, John August. River, from Art in the Christian Tradition, a project of the Vanderbilt Divinity Library, Nashville, TN. https://diglib.library.vanderbilt.edu/act-imagelink.pl?RC=58577 [retrieved January 2, 2022]. Original source: www.JohnAugustSwanson.com - copyright 1997 by John August Swanson.

Comments