Fencing Tables -- Reflections about Restrictions to Gathering at the Lord's Table

Note: This post presents a chapter in a book I'm currently working on titled Eating With Jesus. My goal here is to argue for a fully open Table, as observed by Jesus. This chapter takes note of the efforts through history to fence the table, a process that began at least as early as the 2nd Century if not before.

**********************

It’s unclear whether the first-century followers of Jesus limited Table fellowship to initiated believers. There was some debate within the community about Jewish and Gentile Christians sharing the Table, as Paul points out in the Galatian letter. There he writes about confronting Peter who withdrew from eating with Gentiles while visiting the church in Antioch after being criticized by Jewish Christians (Gal. 2:11-13). What is being referred to in 1 Galatians isn’t the Lord’s Supper, but meals in general. But it does have implications for our gatherings at the Lord’s Table. Paul also speaks about behavior at church meals, which include sharing bread and wine, in 1 Corinthians 11. When Paul speaks in 1 Corinthians of eating unworthily, Paul has the misbehavior of some of the participants in mind. As Ernst Käsemann, reminds us, Jesus tended to gather around himself the kinds of people who might have been deemed unworthy, that is “the fallen, the weak, and the guilty.” Thus, what Paul calls unworthy is different from what we might call it. Therefore, as Käsemann points out, Paul isn’t “referring to the internal state of members of the congregation, but rather to their behavior at the love feast. Those persons do not behave adequately—that is, they behave contrary to the Lord and his cross—who, at Jesus’ table, do not wait for their fellows, who where possible, feed them with leftovers or let them go hungry, while e they themselves feel raptured to heaven and noisily announce their salvation.”[1] That is, the affluent members of the Corinthian community appear to have gotten drunk with wine and ecstasy, while the rest of the congregation went hungry (1 Cor. 11:17-34).

Although

the New Testament doesn’t specifically speak of prerequisites for coming to the

Lord’s Table, such as baptism, by the second century C.E. the fences began to

go up. We see the fencing of the Table clearly revealed in the Didache, an

early manual on the Christian life that originated in Syria, which some

scholars date to the first century C.E. The author of the Didache explicitly

restricts access to the Table to those who have been baptized. That tradition

has continued largely unimpeded to the present, though adjustments have been

made, especially among those traditions that practice infant baptism. When I

was growing up in the Episcopal Church in the 1960s and early 1970s, access to

communion required not only baptism but confirmation. Today baptism and

confirmation might not always be required, but many will restrict access to the

Table to those who profess faith in Jesus. In other words, this is essentially

a “believer’s table.”

If

we start with the Didache we can follow the fencing of the

Table through the years. The unknown author of the Didache offers

this instruction concerning the reception of eucharistic elements: “Allow no

one to eat or drink of your Eucharist, unless they have been baptized in the

name of the Lord. For concerning this, the Lord has said, ‘Do not give what is

holy to dogs.’” (Didache 9:5).[2]

While

the Didache limited partaking of the Supper to those who are

baptized, as time passed, the restrictions became even narrower as one must be

baptized not only to receive the Eucharist but to be present for it. Baptism

followed a lengthy period of catechesis. Writing in the middle of the second

century C.E., Justin Martyr describes the progression from baptism to the

Eucharist.

Writing

in his First Apology, a defense of the Christian faith, Justin

shares that after a person/persons who have been baptized have been brought to

the place where the Eucharist/Supper is to be received, “bread and a cup of

water and mixed wine are brought to the president of the brethren and he,

taking them, sends up praise and glory to the Father of the universe through

the name of the Son and of the Holy Spirit, and offers thanksgiving at some

length that we have been deemed worthy to receive these things from him. When

he has finished the prayers and the thanksgiving, the whole congregation

present assents, saying, ‘Amen.’ At that point, the deacons distribute to those

in attendance the bread and cup.”[3] Justin reaffirms the practice of the

congregation of which he is a part: “This food we call Eucharist, of which no

one is allowed to partake except one who believes that the things we teach are

true, and has received the washing for forgiveness of sins and for rebirth, and

who lives as Christ handed down to us.” Why is this? It is because this

community does not hold these elements to be common food or drink. Instead,

they affirm that these elements are in fact “Jesus Christ our Saviour being

incarnate by God's word took flesh and blood for our salvation.” They

understand the elements to be sacred food and drink, such that the “food

consecrated by the word of prayer which comes from him, from which our flesh

and blood are nourished by transformation, is the flesh and blood of that

incarnate Jesus.”[4] Justin writes that this belief

system is to be found in the Apostle’s memoirs or Gospels. He also contrasts

the Christian rites with those of the followers of Mithra, who also include in

their rites bread and wine.

The

common practice of the early church was to require a period of catechesis,

usually three years, (instruction) followed by baptism before a person was

admitted to the communion service. Manuals such as The Apostolic

Tradition, which is attributed to the third-century church leader

Hippolytus, and the later Apostolic Constitutions tell us that

after the service of the Word, but before the Eucharist, catechumens and

penitents would be dismissed before the Eucharist proper began.[5] As for the period of catechesis, it

might take as long as three years.

One

reason that the church begins to restrict participation in the Eucharist is the

developing realism of Jesus’ presence in the Eucharist. These developments,

which we find present in the second century in leaders such as Irenaeus, who

used claims of Jesus’ being present in the elements as a way to demonstrate the

true humanity of Jesus to counter Gnostic claims concerning Jesus. Irenaeus

isn’t concerned with offering a fully developed eucharistic theology. Moving

forward into the third century, for the most part, the Eucharist remained part

of a larger meal. That began to change, however, as Christians began to gather

in larger rooms. Perhaps as early as the late second century, and certainly in

the third, as Christians moved from evening gatherings to Sunday morning, the

Eucharist became separated from the meal. Access to that meal, however,

remained limited to the baptized, as catechumens would be dismissed from the

service before the Eucharist was served.[6] At the same time, in most early

Christian writings on the relationship between baptism and the Eucharist, the

Eucharist functioned as the culmination of the initiation process.

While

both Eastern and Western churches affirmed the real presence, Eastern churches

did not embrace the doctrine of transubstantiation or the Aristotelianism on

which it was based. Nevertheless, both East and West limited access to the

Eucharistic elements. Aspects of Eucharistic theology, including real presence,

sacrifice, and conversion of elements, whether understood in terms of

transubstantiation or not, contributed both to decreasing frequency of people

receiving communion, as well as more limits placed on one’s ability to

commune.

Theological

concerns, especially around partaking unworthily, led, especially after the

late fourth century, to people choosing not to commune on every occasion that

they attended the Eucharist. This increased as time passed. Being taught that

if they partook unworthily (1 Cor. 11:27-32) they could end in damnation,

people chose not to receive unless they had prepared carefully beforehand by

“purifying one’s life, confessing one’s sins, and receiving absolution first.

It, therefore, seemed safer to restrict oneself most of the time to what became

known as ‘spiritual communion’ —attending the rite but not consuming the

elements.”[7] In terms of spiritual communion, by

the twelfth century, it was understood that the priest could receive the

elements on behalf of the people. As time passed, concerns about accidental

spillage of the wine (consecrated blood of Christ) led to the reception of only

the bread, which often was placed on the tongue by the priest. Theological

rationales were developed to defend these changes.

As

the church moved into the Medieval period, a new rite was added, which would be

the rite of confirmation, which was understood to be an expression of an

apostolic anointing, imposed on a confirmand by the bishop. Laying on of hands

and anointing (chrismation) had long been part of the baptismal formula,

ritualizing the gift of the Holy Spirit to the recipient. During the Middle

Ages, the act of laying on hands and anointing with oil (chrismation), usually

conferred by a diocesan bishop, was separated from baptism. As Thomas Aquinas

writes, the Sacrament of Confirmation came to be understood as a sacrament of

spiritual maturity: “just as Baptism is a spiritual regeneration unto Christian

life, so also is Confirmation a certain spiritual growth bringing man to

perfect spiritual age” [III, Q. 72, Art. 5].[8] For Aquinas and those who follow him,

Confirmation perfects Baptism that has been administered in infancy, and thus

together they serve as the foundation for receiving the Eucharist [III, Q. 65.

Art. 3].

As

we move on to the Reformation, the number of sacraments was reduced to

two—Baptism and the Eucharist—and transubstantiation was rejected as a

theological understanding of how Christ is present in the elements, but

questions of access to the Table did not change. Baptism remained a

prerequisite for access to the Table (confirmation might also be needed, even

if not understood to be a sacrament).

John

Calvin, who, in my estimation has a very attractive understanding of Christ’s

presence in the Eucharistic experience, offers a very narrow view of who could

come to the Table.

We have heard, my brethren, how our Lord observed His Supper with His disciples, from which we learn that strangers and those who do not belong to the company of His faithful people must not be admitted. Therefore, following that precept, in the name and by the authority of our Lord Jesus Christ, I excommunicate all idolaters, blasphemers, and despisers of God, all heretics and those who create private sects in order to break the unity of the Church, all perjurers, all who rebel against father or mother or superior, all who promote sedition or mutiny; brutal and disorderly persons, adulterers, lewd and lustful men, thieves, ravishers, greedy and grasping people, drunkards, gluttons, and all those who lead a scandalous and dissolute life. I warn them to abstain from this Holy Table, lest they defile and contaminate this holy food which our Lord Jesus Christ gives to none except they belong to the household of faith.[9]

Calvin’s restrictions on who is

welcome would guide the positions taken by his followers, who limited access to

the Table to those who were considered worthy. Worthiness was often determined

by church elders.

Alexander

Campbell, a founder of the movement that produced my denomination, the

Christian Church (Disciples of Christ), had something of a conversion

experience. He was in Scotland, while his father had preceded him in the United

States. He had intended to take communion in a local church Presbyterian church

(not the Church of Scotland), having received his token, after being examined,

as he approached the Table, he threw down the token and left without communion,

rejecting this act of fencing the Table. At the same time, his father was being

defrocked by his denomination because he invited Presbyterians living on the

frontier (western Pennsylvania), but not of his sect, to gather for communion.

Fortunately, at least within Mainline Protestantism, such experiences would be

rare.

In

the Modern era, especially after Vatican II, we have seen much convergence in

the theology and liturgical dimensions of the Eucharist. However, the fences

remain in place, even if not always enforced. For Roman Catholics and Orthodox

Churches, one must be members in good standing in those churches to receive the

elements (Vatican II reinstated the reception of the elements in both kinds).

Most Protestant communities, officially, require baptism at a minimum. For most

mainline Protestant churches other than the Disciples of Christ, infant baptism

is practiced. Whereas once confirmation was required in the Episcopal Church

for reception (that was my experience growing up in the 1960s and early 1970s),

now Baptism is the only prerequisite.

Within

the Protestant community, there has been a movement toward mutual recognition

of baptism, such that most Mainline Protestant Churches have opened the Table

to all baptized persons, regardless of their denomination. The important

consensus document from 1982 Baptism, Eucharist, and Ministry, declared

that “mutual recognition of baptism is acknowledged as an important sign and

means of expressing the baptismal unity given in Christ. Wherever possible,

mutual recognition should be expressed explicitly by the churches.”[10] With that in mind, we turn to the

celebration of the Eucharist. The Baptism, Eucharist, and

Ministry document does not directly stipulate opening the Table to all

baptized Christians, but it does not that “it is in the eucharist that the

community of God’s people is fully manifested. Eucharistic celebrations always

have to do with the whole Church, and the whole Church is involved in each

local eucharistic celebration. In so far as a church claims to be a

manifestation of the whole Church, it will take care to order its own life in

ways which take seriously the interests and concerns of other churches.”[11] I would suggest that these

agreements lower the fences, somewhat, encouraging greater eucharistic

fellowship, but fences continue to exist. Many traditions still do not have

full communion agreements, so while the Table might open to the Baptized or

those who believe in Jesus, questions as to who can preside at the Table remain

unresolved.

As

we ponder the current state of Table fellowship, whether frequent or not, we

have historical patterns that continue to influence the way we gather and who

is invited to the Table. Some traditions maintain more restrictions than

others. The question being raised in this book concerns how our Table practices

reflect Jesus’ Table practices. I will acknowledge here that what I am

presenting here is an exception to the traditions that developed over time,

beginning at least in the second century. I would also want to state clearly

that I affirm that baptism serves as the sign and seal of our membership in the

Christian community. Baptism into Christ serves as the sign that we are clothed

with Christ (Gal. 3:27). My expectation is that those who choose to become part

of the community of faith will seek baptism. For those who are baptized, the

Lord’s Supper serves as the ongoing means of grace, for baptism is to be a

one-time event whereas we gather regularly (some more frequently than others)

at the Lord’s Table. While this is true, does that mean one who is not baptized

or does not yet believe should be excluded from the Table?

We

will explore in the next section passages from the Gospel that tells of Jesus’

Table fellowship. These stories can help us better consider how our practices

reflect Jesus’ practices. Before we consider those stories and consider their

implications, I will briefly discuss the question of Jesus’ presence at the Lord’s

Supper.

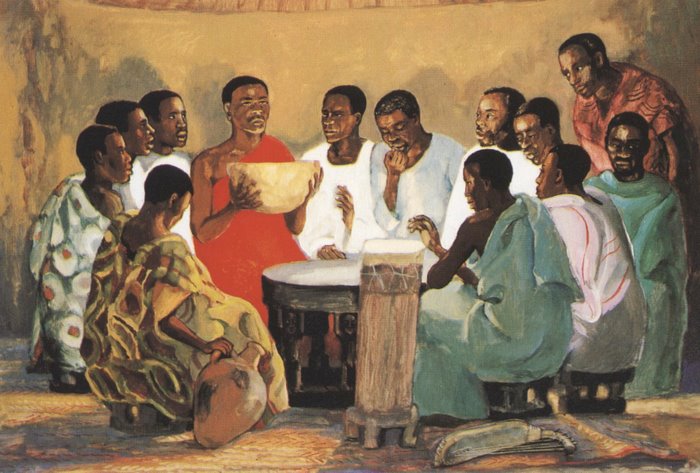

| Image Attribution: JESUS MAFA. The Lord's Supper, from Art in the Christian Tradition, a project of the Vanderbilt Divinity Library, Nashville, TN. https://diglib.library.vanderbilt.edu/act-imagelink.pl?RC=48272 [retrieved August 21, 2023]. Original source: http://www.librairie-emmanuel.fr (contact page: https://www.librairie-emmanuel.fr/contact) |

[1] Ernst Käsemann.

Church Conflicts: The Cross, Apocalyptic, and Political Resistance, Ry

O. Siggelkow, ed., Roy A. Harrisville, trans., (Grand Rapids, MI: Baker

Academic, 2021), pp. 122-123.

[2] Tony Jones,

The Teaching of the Twelve: Believing and Practicing the Primitive

Christianity of the Ancient Didache Community, (Brewster, MA: Paraclete

Press, 2009), Kindle Edition, p. 27.

[3] Justin

Martyr, “First Apology,” 65, in Cyril C. Richardson, Early Christian Fathers—Enhanced

Edition, Christian Classics Ethereal Library, Kindle Edition.

[4] Justin

Martyr, “First Apology,” 66.

[5] Paul F.

Bradshaw and Maxwell E. Johnson, The Eucharistic Liturgies: Their Evolution

and Interpretation (A Pueblo Book), (Collegeville, MN: Liturgical Press,

2012), pp. 74-75.

[6] Andrew

B. McGowan, Ancient Christian Worship: Early Church Practices in Social,

Historical, and Theological Perspective, (Grand Rapids, MI: BakerAcademic,

2014), pp. 60-63.

[7] Bradshaw

and Johnson, The Eucharistic Liturgies, p. 210.

[8] Thomas

Aquinas, Summa Theologica (Complete & Unabridged) (p. 4456). Coyote

Canyon Press. Kindle Edition.

[9] John

Calvin, quoted in Paul Westermeyer, “Guess of the Crucified: Still Place for

Self-Examination,” Word & World, 33.1(Winter 2013): 75, 79.

[10] Baptism,

Eucharist, and Ministry: Faith and Order Paper No. 111, (Geneva,

Switzerland: World Council of Churches, 1982), pp. 13-14.

[11] Baptism,

Eucharist, and Ministry, p. 23.

Comments