When God Shows Up—Lectionary Reflection for Pentecost 14A/Proper 17A (Exodus 3)

|

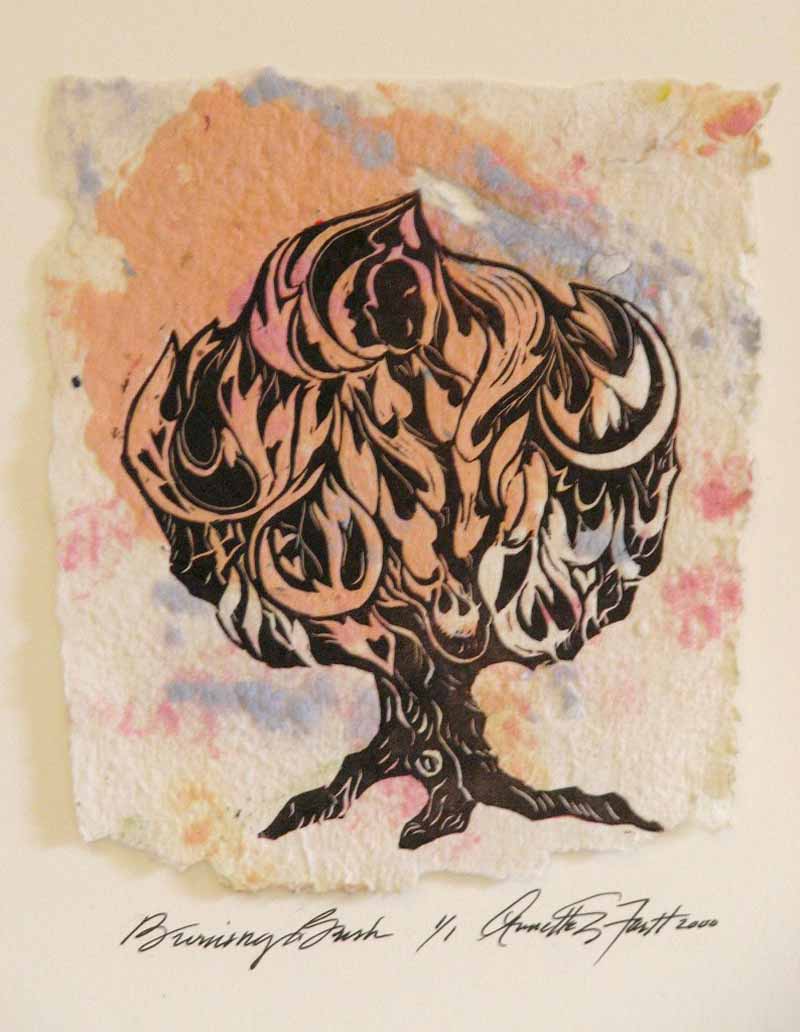

| Annette Gandy Fortt, Burning Bush |

Exodus 3:1-15 New Revised Standard Version Updated Edition

3 Moses was keeping the flock of his father-in-law Jethro, the priest of Midian; he led his flock beyond the wilderness and came to Mount Horeb, the mountain of God. 2 There the angel of the Lord appeared to him in a flame of fire out of a bush; he looked, and the bush was blazing, yet it was not consumed. 3 Then Moses said, “I must turn aside and look at this great sight and see why the bush is not burned up.” 4 When the Lord saw that he had turned aside to see, God called to him out of the bush, “Moses, Moses!” And he said, “Here I am.” 5 Then he said, “Come no closer! Remove the sandals from your feet, for the place on which you are standing is holy ground.” 6 He said further, “I am the God of your father, the God of Abraham, the God of Isaac, and the God of Jacob.” And Moses hid his face, for he was afraid to look at God.

7 Then the Lord said, “I have observed the misery of my people who are in Egypt; I have heard their cry on account of their taskmasters. Indeed, I know their sufferings, 8 and I have come down to deliver them from the Egyptians and to bring them up out of that land to a good and spacious land, to a land flowing with milk and honey, to the country of the Canaanites, the Hittites, the Amorites, the Perizzites, the Hivites, and the Jebusites. 9 The cry of the Israelites has now come to me; I have also seen how the Egyptians oppress them. 10 Now go, I am sending you to Pharaoh to bring my people, the Israelites, out of Egypt.” 11 But Moses said to God, “Who am I that I should go to Pharaoh and bring the Israelites out of Egypt?” 12 He said, “I will be with you, and this shall be the sign for you that it is I who sent you: when you have brought the people out of Egypt, you shall serve God on this mountain.”

13 But Moses said to God, “If I come to the Israelites and say to them, ‘The God of your ancestors has sent me to you,’ and they ask me, ‘What is his name?’ what shall I say to them?” 14 God said to Moses, “I am who I am.” He said further, “Thus you shall say to the Israelites, ‘I am has sent me to you.’ ” 15 God also said to Moses, “Thus you shall say to the Israelites, ‘The Lord, the God of your ancestors, the God of Abraham, the God of Isaac, and the God of Jacob, has sent me to you’:

This is my name forever,and this my title for all generations.

**************

A

Pharaoh arose in Egypt who did not know Joseph (Exod. 1:8). Because the

population of Joseph’s people, the descendants of Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob,

had grown so large, Pharaoh got a bit anxious about his people being displaced

by these outsiders. So, as we discovered in the reading for Proper 16A, Pharaoh

decided to deal shrewdly with this group. He tried to use slavery and forced

labor, but that didn’t work. Then he ordered the Hebrew midwives to kill the

baby boys, but they resisted, and the number of Hebrews continued to grow. Then

he commanded the entire citizenry to throw the baby boys into the Nile, but at

least one family in cooperation with Pharaoh’s daughter resisted, saving one

baby boy. That boy, who became the adopted son of Pharaoh, came to be known as

Moses (Exod. 1:8-2:10).

We pick

up the story in Exodus 3, and if we jump from the previous week’s lection to

this one, we’ll quickly realize there is some information missing. Last we knew

Moses was hanging out with Pharaoh’s daughter, so how come he’s keeping watch

over the flock of his father-in-law, a Midianite priest named Jethro? The

answer is found in the verses we’ve skipped over, Exodus 2:11-25. In those

verses, we learn that when he grew up, Moses rediscovered his Hebrew identity

and when he saw an Egyptian beating a Hebrew slave, he killed him. Then, when

Moses came out to inspect the working conditions of the Hebrews he tried to

intervene in a fight between two Hebrews, who in turn asked if Moses was going

to kill them like he did the Egyptian the day before. Knowing that he had been

identified as a killer, he fled to the desert, where he met Jethro’s daughter,

whose name was Zipporah, fought off some shepherds who were bothering her, got

married to Zipporah, had a son with her, and took up a new vocation of

shepherd. In the meantime, Pharaoh died (in Cecille B. DeMille’s version, the

new Pharaoh is Moses’ step-brother), while the Hebrew people continued to

suffer in slavery. When the people cried out in their suffering, God heard

their cries and remembered the covenant made with Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob.

That sets up the next act in the story, the act in which Moses once again

appears.

Before

we get to Exodus 3, it’s worth pondering this statement that God remembered the

covenant made with Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob. It’s as if God had forgotten

about the people until they cried out in their suffering. Whether God was

attending to other things, now the people have God’s attention. The question is

what will happen now that God has noticed them and is concerned about their

welfare? The New Living Translation offers us some insight with its

version of Exodus 2:25 “He looked down on the people of Israel and knew it was

time to act.” I think that’s a good segue way into the reading from Exodus

3.

The

readings from the Hebrew Bible since the Second Sunday after Pentecost (Proper

5) have focused on the covenant promise made to Abraham and his descendants,

which promised that God would bless the nations through Abraham’s descendants.

By the time we get to the Book of Exodus, it appears as if that covenant

promise is increasingly under threat. If God forgot, well then surely the

people had forgotten, especially in light of their oppression at the hands of

the Egyptians. But, we’re told that God heard their cries, noticed their

suffering, remembered the covenant, and decided to act.

How did

God act in response to the cries of the people? As we pick up our reading from

Exodus 3, Moses is out keeping the flock for his father-in-law. In other words,

Moses was minding his own business with no thought about his previous life. He

had a wife, a child, and even a job. Besides that, it appeared that Pharaoh had

also forgotten about Moses. At least Moses didn’t seem to fear the wrath of

Pharaoh. When Moses was out tending the flock, he came to a place known as

Horeb, “the mountain of God.” Moses noticed a bush that seemed to be burning

but wasn’t consumed. That intrigued him. How could this be? Perhaps we would

act similarly, but Moses had to know more. He wanted to know how a bush could

burn and yet not be consumed. So, he hiked over to where the burning bush sat.

While

Moses sat there pondering this bush, trying to figure out what it meant, he

heard a voice. What Moses is experiencing at that moment is a theophany, an

appearance of the divine. The burning bush is the visible part of the

theophany. While a burning bush is an interesting sight, by itself it’s just an

enigma, a curiosity. But when a voice speaks from within the burning bush, now

we have something to pay attention to. The voice calls out to Moses by name.

Moses answered: “Here I am.” Walter Brueggemann writes of this initial

exchange, that it “establishes the right relation of sovereign and servant.

This is the first hint we have that the life of Moses has a theological

dimension, for the categories of his existence until now have been political”

[Brueggemann, “The Book of Exodus, New Interpreter’s Bible, 1:712].

After

the right relationship between God and Moses has been established, the voice

invites Moses to come closer, while instructing him to remove his sandals

because he was standing on holy ground (cue the music). The reason this ground

is holy is that God is uniquely present in this place. This holiness reflects

God’s nature. By taking off his sandals, Moses acknowledges God’s holiness,

along with the holiness that this place takes on.

Now

that the setting of the conversation is firmly in place because God is present,

making the space where God is present holy, and Moses has acknowledged God’s

presence and holiness, we’re ready to hear God’s revelation of God’s identity.

The voice that calls out from the burning bush declares: “I am the God of your

father, the God of Abraham, the God of Isaac, and the God of Jacob.” In other

words, I am the God who made a covenant with Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob. The

good news is that I’ve remembered that covenant because the people have cried

out amid their suffering. Thus, this revelation is a reminder to the reader (as

well as to Moses), that God is a covenant-making God.

It is

as the covenant-making God, that God reaches out to Moses. God tells Moses that

the misery of God’s people has been noticed. Their cries have been heard on

account of their taskmasters. Yes, God has observed and has come to understand

the nature of this people’s suffering. Now, God is ready to deliver them. Not

only will God deliver them, but God is going to lead them to a land “flowing with

milk and honey.” While this land is currently occupied by Canaanites, Amorites,

Perizzites, Hivites, and Jebusites, Moses doesn’t need to worry about that. God

will take care of things at that end. This revelation is problematic because it

suggests that even as the Hebrews had become an oppressed people in Egypt, God

was placing them on a path where they would displace people already living in

this promised land. While we can see (or hopefully can see) the dangerous

implications of this revelation to Moses, it wasn’t on the mind of the people

reading this, for the readers of Exodus already lived in the land (sort of like

European Americans have lived in land previously inhabited by Native

Americans). The focus here is on the relief to be given to God’s oppressed

people.

We

might wonder why, if God is omnipotent, God couldn’t just deal with Pharaoh and

free the people. In fact, why did God allow the people to be enslaved in the

first place? Of course, the author(s) of Exodus don’t have those kinds of questions

in mind. What the author(s) want us to focus on is God’s decision to act and

that this act would involve Moses. Yes, God tells Moses “I will send you to

Pharaoh to bring my people, the Israelites, out of Egypt” (Ex. 3:10).

The problem here is that Moses isn’t quite

sure who is speaking. Apparently, he hadn’t learned about his ancestors in

Sunday School. Remember that Moses was raised in Pharaoh’s court and now lived

among the Midianites. He might not know much about the covenant-making God. So,

Moses asks for more information if he’s going to accept God’s call to go to

Pharaoh (remember that according to the story Moses is a fugitive) and demand

that Pharaoh let God’s people go. So, first off, he wants to know why God would

want to use him. Yes, “who am I?” Reading between the lines, Moses might be

content with his current life. Shepherding might not be glamorous, but he had a

wife and child. Life was good. Why upset things and head to Egypt and confront

Pharaoh on behalf of this people whom Moses had never really known?

Of

course, God has an answer for Moses. Not to worry, while the deliverance of the

people will be on your shoulders, “I’ll be with you.” In other words, when God

acts it’s in partnership with humans. So, Moses responds to this offer with

another question. Who is it that I’m supposed to say is sending me? It appears

that this talk of being the God of Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob, wasn’t enough. He

might understand this talk of ancestors, but Moses wants a name. Give me your

name. In the ancient world, knowing the name of a god meant having some power

over that deity. Perhaps Moses wants a bit of insurance that God will be true

to the promise.

God’s answer

to Moses’ request is intriguing because it both hides God’s identity and reveals

it. God tells Moses “I am, who I am.” So, tell them “I Am” sent you. Now, many

scholars believe that there is a better way of translating God’s statement.

They suggest a more dynamic translation such as “I Will Be Whoever I’ll Be.” I

appreciate this word from Jewish psychologist David Arnow, who suggests that

the translation of the divine name—Ehyeh-Asher-Ehyeh— as “I will be what

I will be” “epitomizes God’s capacity for change.” That is God will be what God

will be implies that God is not static, but rather dynamic, changing,

evolving.” He then writes that because we are created in God’s image, “ we

share God’s capacity to evolve. Past and present need not define who we will

be. Hope inhabits an open future” [Arnow, Choosing Hope, p. 19]. However

we decide to translate the given name of God, Walter Brueggemann makes an

excellent point that the formula speaks of power, fidelity, and presence. Thus:

“This God is named as the power to create, the one who causes to be. This God

is the one who will be present in faithful ways to make possible what is not

otherwise possible. This God is the very power of newness that will make

available new life for Israel outside the deathliness of Egypt” [NIB, 1:714].

Thus, this is a theological interpretation, not a philological one. As for

Moses, it’s not likely that this response cleared things up. Nevertheless, it

does appear to be sufficient because Moses doesn’t ask any more questions. The

reading closes with a word from God: “This is my name forever, and this is my

title to all generations” (Ex. 3:15).

So,

what are we to take from this reading? Lincoln Galloway may offer us a few

insights:

For us today, our mountaintop experiences or sacred spaces and divine encounters are not just for our edification, but an opportunity to work for the salvation and liberation of a community. For Moses, this moment on holy ground would mark the beginning of divinely initiated and orchestrated venture into liberation and new life for the people of Israel. Holy ground may very well be associated with social justice and activism, communal salvation, and liberation. [Connections: A Lectionary Commentary for Preaching and Worship (pp. 606-607). Kindle Edition.]

Our divine encounters

and time in sacred spaces can be spiritually invigorating. We may feel close to

God when we enter holy places, whether they are designated holy places or

places in nature. But where does that take us? For Moses that meant leaving

behind a comfortable life in Sinai to take on a major calling to liberate his

people from oppression. We may not be tasked with something quite so demanding,

but it would seem that our divine encounters would empower us to participate

with God (remember God promises to go with Moses) in liberating actions. Those

actions might lead to spiritual freedom and encouragement (salvation) or acts

of justice. Each of us, if we’re attentive to the burning bushes in our lives,

will find places to serve. So, the question we all face is whether we’re ready

to answer God’s call with “Here I am, send me”?

| Fortt, Annette Gandy. Burning Bush, from Art in the Christian Tradition, a project of the Vanderbilt Divinity Library, Nashville, TN. https://diglib.library.vanderbilt.edu/act-imagelink.pl?RC=56022 [retrieved August 24, 2023]. Original source: annettefortt.com. | |

Comments