Spring Sprung in 1964 -- Sightings

Being an ecumenical person -- after all, I chair my region's Ecumenism Commission and am Convener of the local interfaith group -- I am always interested in reports on the state of the ecumenical movement. In many ways the movement is in a death spiral -- at least from an institutional perspective -- but in other ways it's going strong (in a much more informal way).

Although I'm a Protestant, like many Protestants, I have an interest in Vatican II, in large part because it changed the dynamics of Protestant-Catholic relationships. Like many, both Protestant and Catholic, I'm concerned that there is a move in the Catholic Church away from the ecumenical vision enunciated by the Council. Next fall, we will note the fiftieth anniversary of this important Council, but this anniversary, combined with the current state of the ecumenical movement, raises questions -- what does ecumenism look like in the 21st century. This is the question Michael Reid Trice raises in today's issue of Sightings.

***************************

Sightings 5/10/2012

Spring Sprung in 1964

-- Michael Reid Trice

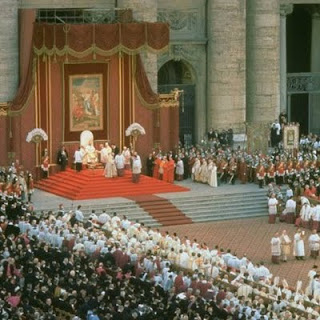

Next October Christian communities will begin a “year of faith” by marking the fiftieth anniversary of the Second Vatican Council. That council took place astride the monumental ripsaw challenges to modern ecclesial life, and widely within the thematic twin trajectories of the nature of being Church (Lumen Gentium) and the future of that Church in the Modern World (Gaudium et Spes). Even as these two documents were framed within the Council itself, their thematic resonance was evident throughout the entire Council. That autumn fifty years ago began an ecumenical spring.

Within that spring, numerous documents were drafted, including the foundational 1964 Decree on Ecumenism (Unitatis Redintegratio), which represented ecclesial liquid fuel to the modern global ecumenical movement, via a global increase in bilateral and multilateral dialogues that followed in the past fifty years. The optimistic hope of Unitatis Redintegratio roused “Christian communions” who “everywhere [and in] large numbers have felt the impulse of this grace, and among our separated brethren also there increases from day to day the movement . . . for the restoration of unity among all Christians.”

In terms of world Christianity, these dialogues both hit their mark for fortifying essential global conversation,and largely missed the target in terms of the reception of these very dialogues into local communities. In the stratified denominational and conciliar contexts within the United States, full communion agreements between Lutherans, the Reformed and Episcopalians were not strategically placed in digestible form for local communities, which led to an increase of a well-meaning professional ecumenism that lacked a strategy for ecumenical reception.

In the past fifty years, a further difficulty pervaded, in what Walter Cardinal Kasper identified as a “two-speed ecumenism,” wherein national dialogues were not paid the balance of respect due them and were seen at a lesser speed to the ones that the Vatican initiated with global conciliar entities. All in all, disconnects appeared between the local-national-international ecumenical contexts that are still not easily overcome.

But that was 1964, and 2012 looks quite different for three reasons: First, mainline denominational life in the United States is shrinking and/or embroiled in a discourse around sexual morality that creates unprecedented turmoil. Second, conciliar ecumenism is under duress; even as new conciliar models arrive (such as Christian Churches Together), some national conciliar organizations are at this moment fighting for their future. The ecumenical gears for the twentieth century need refitting for the twenty-first. And third, as more ecumenical offices and councils shift to include interreligious portfolios, the relevant future of the Vatican II Spring will rest in the translatable accessibility of key documents to a post-modern context, in particular those documents on religious freedom and interreligious relations to the Church. Consider the 1965 texts, Decree on Religious Liberty (Dignitatis Humanae) and (Nostra Aetate), for instance. Ultimately, ecumenists must sharpen their methodological hardware for a Christian context where the conversation is more sequestered, on the one hand, and is taking place within the complex worlds of multi-cultural and religious pluralism today, on the other.

In the spring of 2012, I discussed alongside many executives from conciliar ecumenism a specific kind of fear in church and society today. Our creative impulse as a Church amidst dread disguised as a tyranny of the urgent means that our creative responses shrink. We may discover ourselves turning regularly to a grammar of diminishment, of mourning what is lost, of a theology of presentism and a homiletics of consolation, instead of rejecting tyranny in favor of the gospel message of hope that is closer to us than our own hearts, and much nearer than dread.

At an operative level, Christians in the United States must commit to numerous agendas, including: identifying and pursuing together the adaptive realities of being Church today, assessing and creating non-redundant cooperative capacity within complementary structures, and framing emerging opportunities for unified awareness and voice alongside other religious partners.

In the twenty-first century, we know that the Church’s ecumenical engagement in local, national and global environs will necessitate a call for renewal and an integrated ecclesial voice in response to the challenges of our time. Renewal will take courage of an undaunted kind, and not a new jargon that plays on the tired theme of an ecumenical winter. What we need is a new game plan. And one that responds to the clear challenges of our historical moment in the life of the Church.

Michael Reid Trice is Assistant Dean of Ecumenical and Interreligious Dialogue at the School of theology and Ministry at Seattle University.

----------

On the occassion of John Paul II's visit to India in 1999, the Advaitin teacher Swami Dayananda Saraswati addressed a public letter to the pope entitled "Conversion is Violence." The letter, as Reid Locklin summarizes, drew an "absolute contrast ... between 'aggressive, converting' religions like Christianity and Islam and 'non-violent, non-converting' religions like Hinduism." But is it true that Hinduism does not convert? In this month's Religion & Culture Web Forum, Locklin, a Martin Marty Center Senior Fellow in 2010-11, explores "whether and in what respect modern Advaita movements may be said to advocate religious conversion"; and he identifies "a key methodological defect in the controversy: namely, a univocal concept of conversion." Locklin also suggests ways that "an Advaita theology of conversion might ... offer resources for reconsidering, reimagining and redescribing conversion to Christ, on the model of that most famous of converts, the Apostle Paul." Read Up, Over, Through: Rethinking "Conversion" as a Category of Hindu-Christian Studies.

----------

Sightings comes from the Martin Marty Center for the Advanced Study of Religion at the University of Chicago Divinity School.

Comments