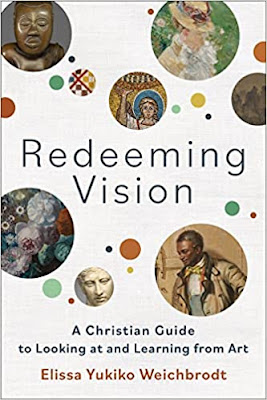

Redeeming Vision: A Christian Guide to Look at and Learning from Art (Elissa Yukiko Weichbrodt) - A Review

REDEEMING VISION: A Christian Guide to Looking at and Learning from Art. By Elissa Yukiko Weichbrodt. Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Academic, 2023. 266 pages.

They

say that art is in the eye of the beholder. Some prefer more contemporary art,

which might be quite abstract. Others prefer more realistic artwork. While

photography might be considered realistic, it can be displayed in ways that are

less straightforward than perhaps a painting. Understanding how to view or

experience artwork, whatever its form, requires a degree of education or

training or simply experience. I’ve been fortunate in recent years to live in a

region that features a world-class art museum—the Detroit Institute of Art.

When we travel to places like Chicago or Cleveland, we have the opportunity to

spend time with great art. Great art can speak to us in many ways—spiritually,

politically, etc. The Detroit Institute of Art features a mural by Diego Rivera

(husband of Frida Kahlo) that describes in great detail the Detroit automotive

industry. It has political implications, as Rivera was known to have Marxist

leanings, something critics brought up. Of course, the DIA has many medieval

paintings that are quite religious, but these murals when experienced in person are powerful witnesses to the relationship of humans and machines.

|

| Diego Rivera Mural, DIA |

When it comes to viewing art, I’ve never been specifically trained to view it. However, the more time spent in various spaces, including museums, I developed a certain level of appreciation. But more can be learned. That’s where Redeeming Vision by Elissa Yukiko Weichbrodt comes in. She writes from a Christian perspective, offering guidance to other Christians to view art in appreciative ways. In doing so she helps us view art through a theological lens, whether the artwork is religious in orientation or not. While she doesn't speak to the Rivera mural, I will view it through a different lens the next time I visit the DIA (and I always spend time in the hall featuring the mural covering all four walls.

The

author of Redeeming Vision, Elissa Yukiko Weichbrodt, is an associate

professor of art and art history at Covenant College. She holds a Ph.D. from

Washington University in St. Louis. She writes in the introduction to the book

that this book is about more than speaking to those who go to art museums.

While the book speaks to that part of our experience of art, she has more in

mind than museumgoers. She writes for all of us who look at pictures. By this

she means viewing Instagram photos, magazines, and graphic novels, to name a

few forms. She asks us "What does your faith have to do with how you

see?" (p. 9). That is, “How does being a Christian transform the ways you

look at art . . .?” When she asks these kinds of questions, she’s not speaking

in terms of guardrails. That is, she’s not attempting here to tell us what not

to see. Thus, she's not interested in the question of whether depictions of

violence or nudity should be avoided.

Instead

of writing about fences, Weichbrodt speaks of ways in which our faith can serve

as a lens through which we view pictures, including artwork. She writes with

the assumption that we are more than viewers, but that are also makers. That

is, she believes we should ourselves as culture makers. She writes that

"when we look at art and images, we can do something with them. We are not

simply consuming visual information or waiting for an artwork to stir our

complacent souls." Our viewing of pictures/artwork might lead us to a

position of lament, or it could create curiosity or even delight. Central to

her message is that "Our viewing becomes making when it grows our love for

God and our neighbor" (p. 11).

Weichbrodt

divides her book into three parts. Part 1 simply helps us learn "How to

Look." In this section of her book, the author provides us with a toolbox

that we can use to engage in the visual analysis of pictures, art, and sculpture.

She introduces us to such formal elements as line, shape, form, color, value,

space, and texture (chapter 1). These tools will be utilized elsewhere in the

book. Chapter 2 is titled “The Archive.” By that, she has in mind our past

experiences in life and with art, which gives us a foundation for interpreting

and experiencing what we see. That is, the archive is the lens through which we

make meaning as we view pictures, whether a photo, sculpture, or painting. This

is like a mental filing cabinet that we rifle through when we view something.

Both the viewer and the artist have archives through which we view things,

giving a context to understand and interpret what we see. In this chapter, the

author uses a famous photo— "Migrant Mother" —as an example, helping

us see things we might not otherwise see. The archive speaks to similar things

we've seen and those that are different. Again, she’ll return to the concept of

our archive throughout the book. Finally, in chapter 3, Weichbrodt speaks of

the frame, or the physical context, in which the picture appears. Here she uses

as a case study, Caravaggio's "The Deposition." She compares the

original setting in a chapel over the altar, where a copy now appears, and the

current location in the Vatican Museum. The question here concerns how context

influences the way we view something, whether in a museum, online, or in its

original location. She suggests that the frame shapes our experiences of the

image.

Having

set the foundations for viewing pictures/art, in Part 2 we move into more

theological dimensions of this study. She titles this section "Love the

Lord your God." In these three middle chapters, she asks us to consider

how the way we view art and images helps grow our love of God. She begins this

section in chapter 4 with a discussion about "Confessing Our Idols."

This chapter includes a conversation about the iconoclastic debates of earlier

centuries, but that's not the primary point. More specifically she speaks of

the idols of the perfect self and the ideal. She suggests, for example, that

the “idealized form, built according to mathematical ratios, proposes a world

where we become gods” (p. 101). Thus, idols need to be cast down. From there we

move into chapter 5, where she offers us a conversation titled "Wondering

at God's Transcendence." In this chapter, Weichbrodt speaks about

transcendence in relation to abstract art, with a focus on Kandinsky's

"Painting with Green Center." The conversation concerns how we might

see something lying beyond the material, so that transcendence can be sensed in

art. If Chapter 5 speaks of divine transcendence in connection with abstract

art, chapter 6, which is titled "Delighting in God's Presence,"

focuses on representational art. In this chapter, which examines representational

art, Weichbrodt speaks to divine immanence. Thus, we explore art that speaks to

mundane things like a vase of flowers or an impressionist painting of a woman

knitting, asking how these pieces reveal something about God.

Part

3 focuses on the call to "Love Your Neighbor as Yourself." This

section is composed of five chapters, beginning with chapter 7, is titled

"Growing Curiosity" and focuses on portraiture. Regarding

portraiture, the questions raised here have to do with the self, both public

and private. So, how do portraits invite curiosity about those pictured? What

do they generate within us? As we ponder these questions, we can better

appreciate our neighbor. Chapter 8 is titled "Sharing Our Space" and

explores landscape art. Landscapes speak of place and location. Our sense of

identity is related to the spaces we inhabit. Thus, what do landscapes say to

us? Then in chapter 9, titled

"Allowing for Complexity" the author explores the “Art of the

Everyday." She points out that simplicity can conceal something important

that requires some reflection. In this regard Weichbrodt points to William

Sidney Mount's "The Power of Music," a painting that focuses on a

barn. Inside are three white men, one of whom is playing a fiddle, while the

other two listen. In the foreground, outside the door, hidden from the three

white men, is a Black man, who is also listening. What does the artist want us

to see in this picture? Is he speaking to the segregated nature of this scene,

such that the Black man is not welcome to join the other listeners? It's a very

interesting conversation. The question here has to do with the complexity

present in a scene, allowing us to explore what might be intended. The

penultimate chapter (Chapter 10) is titled "Learning to Lament," and

is subtitled "The Art of History." Here she explores how art is used

to tell the story of history, using among others an ancient Assyrian scene that

speaks of the Assyrian conquest of the Elamites along with an engraving made by

Paul Revere of Henry Pelmham's "The Boston Massacre." Here she notes

how Revere used this image in propagandist ways to support the cause of the

revolutionaries, showing the British soldiers to be the bad guys.

The

final chapter, titled "Redeeming Vision," draws the preceding

discussion to a close, helping us put together everything we've seen in the

previous chapters. Weichbrodt asks us to consider this question "How do we

look redemptively at a photograph that perpetuates a lie? Can a contemporary

artwork that is a literal crack in the ground suggest a way forward?" (p.

236). Here she starts with a photo by John Choate titled "Tom

Tolino---Navajo" It is a piece that features two pictures of Tom Tolino,

one pictures the man as he entered the Carlisle School, looking very much like

a Navajo. The second picture comes after Tom finishes school. In this picture, Tom

is dressed in a suit with his hair cut short. These pictures were used to show the

viewer how this man had been civilized by attending this school. But is this a

true story? That is, does this picture tell the truth about a man or does it

offer a Westernized vision of what a man living in the United States was

supposed to look like? This raises the question of what happened at boarding

schools like Carlisle that were designed to kill the Indian to save the man.

The second piece is a photograph of the installation of Shibboleth, which is a

crack created into a museum floor, which the author connected to the

experiences of recent immigrants and the dangers of crossing borders (falling

into the crack). In the end, there is a restoration, in which the rack is

fixed, but not erased. Such is our reality. Things can heal but not be erased.

The scars remain.

Elissa

Yukiko Weichbrodt’s Redeeming Vision is a beautifully illustrated book (on

glossy, high-grade paper we would expect from an art book) that should provide

readers with important tools to explore images and see what is shared more

deeply. She writes the book for Christians with the hope that it might help us look

appreciatively at images, doing so through a theological lens that reveals our

love of God and neighbor. Sometimes art is understood to be something to be

enjoyed by the educated elite, but the reality is, we can all enjoy art,

whatever our background. The Detroit Institute of Art is located in a

predominantly Black city, with high poverty rates. While many who visit the

museum come in from the suburbs much as I do, the DIA makes sure that the

students in the Detroit School District have the opportunity to visit the

museum and learn and experience what is found there, inspiring these students,

many of whom come from poor families, to let loose their imaginations. The book

is also a helpful contribution to the current political debates that are taking

our schools hostage, seeking to limit exposure to the larger world. We only

need to consider the decision to exclude from view a picture of Michelangelo’s David

because the school leaders considered it controversial. Why was it deemed

controversial? Well, David is nude, and we can see his penis. Perhaps some who

read Redeeming Vision closely can get beyond such myopic views. For

others of us, she gives lenses by which we can be inspired to love God and

neighbor through our encounters with images and art, as we do we can become culture

makers and not just enjoyers of culture!

Comments