By His Wounds, We Are Healed - A Lectionary Reflection for Easter 4A (1 Peter 2)

1 Peter 2:19-25 New Revised Standard Version (NRSV)

19 For it is a credit to you if, being aware of God, you endure pain while suffering unjustly. 20 If you endure when you are beaten for doing wrong, what credit is that? But if you endure when you do right and suffer for it, you have God’s approval. 21 For to this you have been called, because Christ also suffered for you, leaving you an example, so that you should follow in his steps.

22 “He committed no sin,

and no deceit was found in his mouth.”

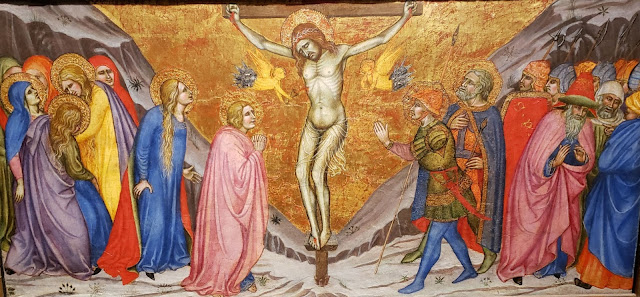

23 When he was abused, he did not return abuse; when he suffered, he did not threaten; but he entrusted himself to the one who judges justly. 24 He himself bore our sins in his body on the cross, so that, free from sins, we might live for righteousness; by his wounds you have been healed. 25 For you were going astray like sheep, but now you have returned to the shepherd and guardian of your souls.

****************

As I write this over two million people around the world are or have been suffering the effects of a novel coronavirus outbreak. Tens of thousands have died, with the numbers climbing every day. There is no vaccine and treatments that look promising seem to fall short on every front. Stores, schools, and faith communities are all shut down. Holy Week and Passover were observed in ways no one can remember. Now Muslims observe Ramadan in the same fashion. Daily life is not what it was, and whatever emerges after the worst is over will not be the same. We will not be the same. Some will be embittered by their experience, while others will be strengthened.

In this passage from 1 Peter 2, Peter addresses the suffering experienced by his audience. He distinguishes between those who suffer justly and suffer unjustly. If you suffer for doing wrong, then you probably are getting what you deserve. But, for those who suffer unjustly, for righteousness, well that’s different. Getting back to the pandemic, we tend to distinguish between those who get the virus when flouting the recommendations from those who contract it and even die for no fault of their own. This is especially true for those front-line folks in hospitals, nursing homes, first responders, grocery workers, and others whose jobs have been deemed essential. The word here is that if you do what is right and endure in the midst of it, then you receive God’s approval.

Peter then points to Jesus, not as a substitute but as an example. Therefore, he encourages his readers to follow in the steps of the one who “committed no sin, and no deceit was found in his mouth,” and when he suffered, as a result, he didn’t return abuse on his abusers. In making this statement Peter is drawing on Isaiah 53 and the vision of the suffering servant. The challenge posed by this passage is that it seems to suggest that there is redemptive value in suffering so that suffering is glorified. Contextually, the call to follow the lead of Jesus comes as part of a word given to slaves, who are told to obey their masters. The creators of the lectionary, however, have chosen to omit what is, in reality, the thesis statement of the passage. I understand why the lectionary creators chose to omit verses like this, but as Barbara Lundblad notes, the inclusion of the verse gives preachers “permission to talk about the need for biblical interpretation.” She suggests that it might give preachers and teachers to consider the impact of passages like this on persons who have suffered abuse and hear that they should endure the abuse as Christ endured abuse [Feasting on the Word, 437]. What was heard by Christians living in the first century when they were a religious minority, struggling to survive in a culture where slavery was a central part of the economic system, over which they had no control. That is different than a context such as antebellum North America where Christians were not a religious minority.

When we approach texts like 1 Peter, which speaks of being servants of God and freedom in Christ, how do we as God’s free people we navigate a society that is not always conducive to our freedom? Verse 18, which is the lead-in to the lectionary reading, instructs slaves to obey their masters, not just those who are kind and gentle, but even the harsh ones. A verse like this was a powerful tool in antebellum America in efforts to justify slavery and oppress those who were slaves. Thus, we must speak against it. We can try to sugar coat it but to no avail. But what about Peter’s context? Why would he write such a word to the church?

When Peter speaks here of freedom, he was thinking of spiritual freedom. He didn’t have in mind, necessarily emancipation from slavery or an end to patriarchy. These were not within the realm of possibility, though manumission was common in the first century. Slavery wasn’t race-based nor was it necessarily permanent. When Peter appeals to the household codes he was drawing on the common cultural understandings, which suggests that Peter was telling the people to keep their heads down, be good citizens, and then perhaps they could be good witnesses for Christ’s kingdom. Thus, interpreting and applying a text like this takes a lot of wisdom.

While the creators of the lectionary decoupled Peter’s instruction to slaves, to make the passage more preachable (or at least more comfortable for preachers who could focus on Christology), we shouldn’t forget the context. If we take into consideration the larger context and disabuse ourselves of thinking that suffering is in itself redemptive, then perhaps we can hear word for today. In fact, we might hear a word of encouragement to persevere, to endure, in the midst of suffering, as we pursue the path that leads to the realm of God.

Peter doesn’t celebrate imperial authority, slavery, or patriarchy, he just assumes that this is the way things are in the world. That is not our context. We have long rejected slavery, and while we might apply some of this to employer-employee relations, even there we need to be careful. At least in my circles, we have set aside patriarchy (or are working on it). As for imperial authority, it is good to remember that in a democracy, the voice of the people is the final authority, not the president. Thus we need to find ways of hearing a word in a passage that contextually poses problems. Nevertheless, we might read a passage like this through a liberation lens. We can read it through the lens of the Civil Rights Movement, which persisted in nonviolent resistance to Jim Crow and segregation, despite facing violent responses. Consider the events that transpired on the Edmund Pettis Bridge in Selma, Alabama. This was suffering endured in a just cause, that eventually overturned injustice.

As for Jesus, he bore our sins that we might be healed. This as we, who “were going astray like sheep, . . . have returned to the shepherd and guardian of your souls.” We needn’t read this through the lens of “penal substitutionary atonement.” That is a temptation, but it’s not a necessary one (I don’t think Peter had worked out a distinct atonement theory here). Instead, we can hear in this word a reminder that we serve the crucified God who suffers with us, and as Bonhoeffer suggests, only such a God can bring healing.

Comments