What About Holy Saturday?

“We’re

you there when they laid him in the tomb?” Before sunset on Good Friday,

according to the Gospels, he was taken from the cross and laid in a tomb. There

are, of course, different versions of this story, but they all agree. Jesus was

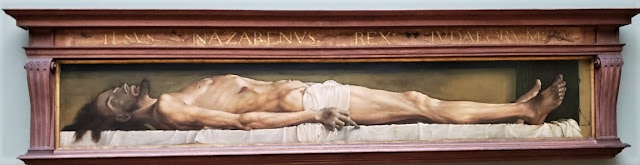

dead and lying in a tomb. This reality is pictured quite vividly in this image of

Hans Holbein the Younger’s “The Dead Christ in the Tomb” (1521-1522). The

painting hangs in Basel’s Kunstmuseum. Cheryl and I encountered it during our

trip to Europe. It’s both fascinating and disturbing to see in person. Even

though this is simply a picture of a painting, I invite you to meditate on it

as you consider the question I raise in the title of the post.

What

happened between the moment of his entombment on Friday evening and the Sunday

discovery of his resurrection? What occurred on Saturday? The Gospels are

silent, except perhaps this somewhat obscure statement found in 1 Peter:

18 For Christ also suffered for sins once for all, the righteous for the unrighteous, in order to bring you to God. He was put to death in the flesh, but made alive in the spirit, 19 in which also he went and made a proclamation to the spirits in prison, 20 who in former times did not obey, when God waited patiently in the days of Noah, during the building of the ark, in which a few, that is, eight persons, were saved through water. 21 And baptism, which this prefigured, now saves you—not as a removal of dirt from the body, but as an appeal to God for a good conscience, through the resurrection of Jesus Christ, 22 who has gone into heaven and is at the right hand of God, with angels, authorities, and powers made subject to him. (1 Peter 3:18-22)

The italicized words in this passage gave rise to the idea

that on Holy Saturday Jesus descended into Hades and rescued those imprisoned

in hell.

We see reference to his “harrowing

of hell,” as it’s known, in the Apostles Creed, The creed (and I should note

that I’m part of a non-creedal tradition)declares of Jesus: “He suffered under

Pontius Pilate, was crucified, died, and was buried. He descended to the

dead. On the third day he rose again.” Much like the reference in 1 Peter,

this declaration seems rather odd, but it reveals that the early church assumed

Jesus was up to something on Holy Saturday. I’m not one to build theologies on

obscure texts like these two, whether scriptural or creedal, but it is

intriguing.

While we

tend to skip from Friday to Sunday, could Saturday’s silence offer a word of

hope for the dead? Could it speak of a hope that lies beyond the grave? The

idea of the harrowing of hell suggests that Jesus used this time to gather the

dead so that they might share in his resurrection? Protestants tend not to

embrace the idea of purgatory, in part because the doctrine had been misused in

the medieval period, but perhaps it might speak to us at this moment. It’s not

that purgatory necessarily must be a “place,” but it can be a way of thinking

that God is not finished with us at death. As Michael Downey writes:

As God’s act beyond our dying and death, purgation describes an intensity of transformation. At our death we are still in need of psychological healing. Different dimensions, or levels, of our self, what Thomas Merton called the “true self,” are as yet unintegrated. Levels of our personality remain disordered and warped. The fullness of life is not yet ours. But it may be by God’s own doing. Rather than a forbidding state, purgatory is a region of hope. [Michael Downey, The Depth of God’s Reach, pp. 79-80].

As I

said above, I’m not one for building theologies on a couple of texts, but I

offer these thoughts as a way of thinking about Holy Saturday and its meaning

for us at this time. Might we find some hope in the silence of the Tomb.

Comments